Unveiling The Orbital Mechanics: Shape And Orientation Of Planetary Orbits

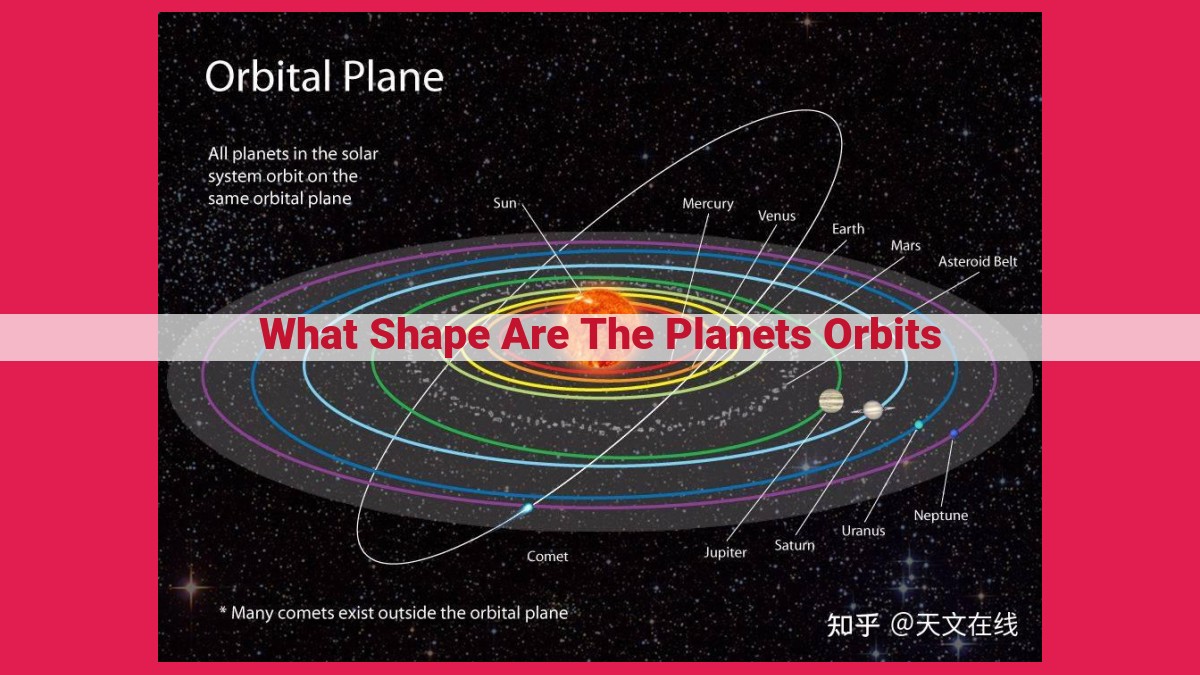

The shape of planetary orbits is determined by their orbital elements, which describe the size, shape, and orientation of the orbit:

– Orbital eccentricity determines how elliptical an orbit is, ranging from 0 (circular) to 1 (parabolic or hyperbolic).

– Orbital inclination measures the tilt of the orbit relative to a reference plane.

– Semi-major axis represents the average distance of the orbiting body from the central object.

– Semi-minor axis describes the width of the ellipse, making it relevant for elliptical orbits.

– Perihelion and aphelion mark the closest and farthest positions of the orbiting body from the central object, respectively.

What is Orbital Eccentricity?

- Definition and description of orbital eccentricity

- Related concepts: Eccentricity Anomaly and True Anomaly

Understanding Orbital Eccentricity: A Key to Unveiling Celestial Motion

What is Orbital Eccentricity?

In celestial mechanics, the concept of orbital eccentricity governs the shape and characteristics of an object’s orbit around a larger body. It is an essential parameter that describes the deviation of an orbit from a perfect circle. Imagine an elliptical path, like a flattened oval, where the orbiting object traces this non-circular trajectory. Orbital eccentricity quantifies how elongated this ellipse is, ranging from zero to one.

Zero Eccentricity: The Perfect Circle

When eccentricity equals zero, the orbit of an object is perfectly circular. This means it follows a uniform path around the central body, maintaining a constant distance. Earth’s moon, for instance, exhibits a near-zero eccentricity, making its orbit appear as a well-defined circle.

Increasing Eccentricity: The Elliptical Dance

As eccentricity increases, the orbit gradually transforms into an ellipse. The more eccentric an orbit becomes, the greater its deviation from a circle. The eccentricity anomaly and true anomaly are related concepts that further describe the object’s position along its elliptical path.

Orbital Inclination: The Tilt Factor

In the celestial symphony of planetary orbits, orbital inclination plays a pivotal role in shaping the celestial dance. It measures the tilt of an orbit’s plane relative to a reference plane, often the plane of Earth’s orbit around the Sun. This tilt adds an extra dimension to the orbital dynamics, creating a captivating choreography of celestial bodies.

A perfectly circular orbit lies flat on the reference plane, with an inclination of 0 degrees. However, most orbits are elliptical, and hence have an inclination that deviates from zero. For instance, Mercury’s orbit boasts a significant inclination of 7 degrees, while Jupiter’s orbit remains close to the reference plane, with an inclination of just 1.3 degrees.

The orbit node marks the intersection point where an inclined orbit crosses the reference plane. From the node, two imaginary lines extend, known as the line of nodes. These lines define a plane that contains both the inclined orbit and the reference plane, providing a reference for measuring the inclination.

Orbital inclination influences various aspects of planetary motion. For example, it determines the eclipses we witness on Earth. When the Moon’s orbit brings it to the same line of nodes where Earth’s orbit lies, a solar or lunar eclipse can occur.

Furthermore, inclination affects the seasonality experienced on planets. A planet with a non-zero inclination will have seasons because as it orbits, different parts of its surface tilt towards or away from the star, leading to variations in sunlight intensity and temperature. Earth’s own inclination of 23.5 degrees gives rise to our familiar seasons.

Orbital inclination, seemingly a small detail in the celestial tapestry, plays a crucial role in orchestrating the movement and interactions of planetary bodies. It adds complexity and diversity to the cosmic ballet, creating a captivating spectacle for our astronomical gaze.

**Semi-Major Axis: Unveiling the Distance Dance in Celestial Orbits**

In the vast cosmic ballet, celestial bodies trace intricate paths around their gravitational conductors. Understanding their orbital parameters is crucial for deciphering their celestial choreography. One such parameter, the semi-major axis, holds the key to measuring the average distance between two orbiting celestial objects.

The semi-major axis, denoted as a, is half the length of the major axis of the elliptical orbit an object traces. Think of an ellipse as a stretched circle, with the major axis being its longest diameter. By dividing the major axis in half, we obtain the semi-major axis, which represents the average distance between the orbiting object and the object it orbits (typically a planet around a star).

The semi-major axis provides a fundamental insight into the period and velocity of an orbiting object. Simply put, the period is the time it takes for the object to complete one full orbit. The velocity, on the other hand, is the speed at which the object travels along its orbit.

The relationship between these orbital elements and the semi-major axis is governed by Kepler’s Third Law. This law states that the square of the period (T²) is directly proportional to the cube of the semi-major axis (a³). In essence, as the semi-major axis increases, the period increases, and the velocity decreases.

It’s as if the celestial bodies are celestial dancers, twirling around their gravitational centers. The larger the dance floor (represented by the semi-major axis), the longer it takes for the dancers to complete one circuit. But with each step, their speed diminishes, as the distance they need to cover increases.

Thus, the semi-major axis serves as a crucial measure, helping us comprehend the dynamic dance of orbital mechanics. It unveils the average distance between celestial bodies, shaping the rhythm of their celestial waltz and providing insights into the celestial symphony that plays out in the boundless expanse of the cosmos.

Semi-Minor Axis: Describing Elliptical Orbits

- Definition of the semi-minor axis

- Related concepts: Latus Rectum and Eccentric Anomaly

Semi-Minor Axis: Unraveling the Elliptical Dance

In the realm of orbital mechanics, elliptical orbits are a common occurrence, where celestial bodies trace an elongated path around a central object. Understanding the properties of elliptical orbits is crucial for unraveling their intricate dynamics, and among these properties, the semi-minor axis plays a significant role.

Defining the Semi-Minor Axis

The semi-minor axis, denoted as “b“, is defined as the shorter radius of an ellipse, perpendicular to the semi-major axis, which joins the two foci of the ellipse. It represents the width or height of the ellipse and is always shorter than the semi-major axis.

Significance of the Semi-Minor Axis

The semi-minor axis provides valuable information about an elliptical orbit:

- Eccentricity: The semi-minor axis, combined with the semi-major axis, determines the eccentricity of an orbit. Eccentricity measures how elliptical an orbit is, with a value ranging from 0 (circular) to 1 (highly elliptical).

- Latus Rectum: The semi-minor axis is closely related to the latus rectum, a constant for each orbit. The latus rectum represents the distance between the focus of the ellipse and the point on the orbit perpendicular to the semi-major axis.

- Eccentric Anomaly: The semi-minor axis is also linked to the eccentric anomaly, a parameter used to describe the position of an object on an elliptical orbit.

Importance for Orbital Calculations

The semi-minor axis is essential for various orbital calculations, including:

- Orbital Velocity: The velocity of an object in an elliptical orbit varies as it moves along its path. The semi-minor axis helps determine the velocity at different points in the orbit.

- Period: The period of an elliptical orbit, the time it takes for an object to complete one revolution, depends on the semi-minor axis and other orbital elements.

Understanding the semi-minor axis empowers scientists and engineers to accurately model and analyze elliptical orbits, enabling them to make precise predictions and optimize spacecraft trajectories.

Perihelion and Aphelion: The Closest and Farthest Points

In the vast expanse of space, objects orbit celestial bodies in paths determined by intricate gravitational forces. Among the fundamental elements that define these paths are perihelion and aphelion, which mark the extremes of an orbiting body’s journey.

Perihelion: The Solar System’s Hot Spot

Imagine our solar system, where planets dance around the blazing sun. When a planet reaches its perihelion, it plunges to its closest point to our stellar companion. At perihelion, the planet is bathed in intense solar radiation, heating its surface and potentially igniting its atmosphere. This phenomenon, observed in planets like Mercury and Venus, has significant implications for their climate and geological processes.

Aphelion: A Distant Embrace

At the opposite end of the spectrum lies aphelion, where an orbiting body ventures farthest from its celestial companion. In our solar system, planets will experience aphelion in their elongated orbits. Mars, for instance, travels its farthest distance from the sun during aphelion, resulting in significant temperature swings and a diminished influence on planetary processes.

Related Concepts: Unraveling the Secrets of Orbital Dance

To fully grasp the significance of perihelion and aphelion, we must explore related concepts:

- Argument of Periapsis: This angle measures the direction from the ascending node to the periapsis (the point closest to the central body).

- True Anomaly at Periapsis/Apoapsis: These angles indicate the exact position of the orbiting body at periapsis or aphelion, respectively.

By studying these elements, astronomers can precisely calculate the trajectory and behavior of celestial bodies, unlocking the mysteries of orbital mechanics and gaining insights into the dynamic nature of our universe.