Understanding Long-Term Assets: A Comprehensive Guide For Business Professionals

Long-term assets, also called capital or fixed assets, are assets held by a business for over a year, used in operations, and not readily convertible to cash. Categories include land, buildings, equipment, investments, and intangible assets. They are classified as non-current on the balance sheet, reflecting their non-liquidity. Depreciation and amortization allocate the asset’s cost over its life to match expenses with revenues. Capitalization occurs when expenditures are recorded as assets, while expensing recognizes costs immediately. If fair value falls below book value, an impairment loss is recognized on the income statement.

Unveiling the Secrets of Long-Term Assets: Your Business’s Foundation for Lasting Growth

Long-term assets, also known as capital assets or fixed assets, serve as the cornerstone of any thriving business. These assets are like the sturdy pillars that support your business’s operations, providing stability and laying the foundation for future growth. Unlike their fleeting counterparts, current assets, long-term assets have an extended holding period exceeding one year, contributing to your business’s long-term success.

Imagine your business as a grand castle, with long-term assets forming its堅固的基石. These include the property, the land upon which it stands, and the machinery that powers your operations. Each brick and mortar, each piece of equipment, represents a long-term investment in your business’s future.

Examples of Long-Term Assets:

- List and describe three main categories:

- Property, Plant, and Equipment (buildings, land, machinery)

- Investments (stocks, bonds, real estate)

- Intangible Assets (patents, trademarks, copyrights)

Examples of Long-Term Assets

In the realm of business, long-term assets are the backbone of operations, providing stability and long-term value. These assets extend their presence beyond a year, serving as pillars that sustain a company’s growth and success. Let’s delve into the diverse categories that encompass the world of long-term assets.

Property, Plant, and Equipment

These tangible assets form the physical foundation of a business. They include:

- Buildings: The structures that house operations, from offices to manufacturing plants.

- Land: The real estate upon which buildings stand, providing a solid foundation for the business.

- Machinery: Specialized equipment that drives production, such as assembly lines and heavy machinery.

Investments

Long-term investments extend a company’s financial reach beyond its core operations. They take various forms:

- Stocks: Ownership shares in other companies, providing diversification and potential returns.

- Bonds: Debt instruments that represent loans to other entities or governments, generating interest payments.

- Real estate: Buildings or land acquired for investment purposes, offering rental income or potential appreciation.

Intangible Assets

Unlike their tangible counterparts, intangible assets lack physical form but are no less valuable to a business. They include:

- Patents: Exclusive rights to inventions or designs, providing a competitive edge.

- Trademarks: Distinctive symbols that identify a company’s products or services in the marketplace.

- Copyrights: Protection for original works, such as literary or artistic creations, securing ownership and creative rights.

These diverse categories of long-term assets play vital roles in supporting the growth and longevity of businesses, providing stability, diversification, and a foundation for future success.

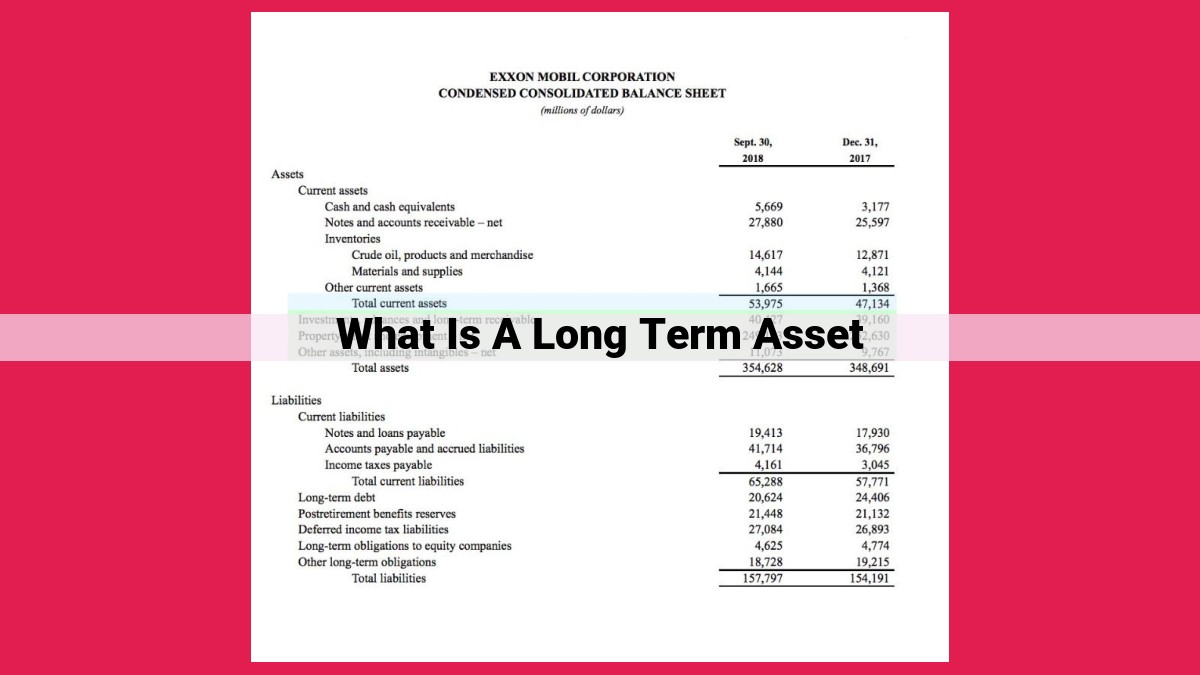

Understanding the Balance Sheet Classification of Long-Term Assets

Storytelling:

Imagine your company’s financial health as a detailed painting. Long-term assets are like the brushstrokes that shape the overall picture, representing your investments in the future. These assets, also known as capital assets or fixed assets, are the building blocks of your business’s long-term success.

Balance Sheet Classification:

On your company’s balance sheet, long-term assets find their home in the non-current assets section. Unlike current assets, which are expected to be converted into cash within a year, long-term assets have a longer lifespan, typically over one year.

The non-current status of long-term assets reflects their non-liquidity. They are not easily convertible into cash, unlike inventory or accounts receivable. This is because they are invested in the core operations of your business, such as buildings, machinery, and patents.

Long-term assets contribute to your company’s long-term earnings potential, but they do not play a direct role in your day-to-day operations. They provide the foundation for future growth and stability, giving your business a competitive edge and increasing its overall value.

Depreciation and Amortization: Accounting for Long-Term Asset Value

When it comes to long-term assets, like buildings, equipment, or patents, businesses need a way to account for their value over time. This is where depreciation and amortization come into play.

Depreciation is the process of spreading out the cost of a tangible asset over its expected useful life. For example, if a company buys a new machine for $100,000 with an estimated life of 5 years, it would record depreciation expense of $20,000 per year for 5 years. This reduces the asset’s book value (the value reported on the balance sheet) while increasing the company’s expenses.

Amortization is similar to depreciation, but it applies to intangible assets like patents, trademarks, and copyrights. These assets do not have a physical form but provide value to the company over time. Amortization spreads out the cost of these assets over their expected useful life, reducing their book value and increasing expenses.

Both depreciation and amortization are essential accounting practices because they match expenses to the revenues they generate. As a company uses its long-term assets to produce goods or services, the cost of those assets should be recognized as expenses in the periods in which the revenue is earned. This ensures that the company’s financial statements accurately reflect its financial performance.

The decision to depreciate or amortize an asset is based on a number of factors, including its materiality (whether its cost is significant enough to warrant recognition as an asset) and the expected benefits it will provide to the company. For example, if a company purchases a small office chair, it may choose to expense it immediately rather than depreciate it over several years. However, if the company purchases a large server that will be used for many years, it would likely depreciate the asset to spread out its cost over its useful life.

Understanding depreciation and amortization is crucial for businesses to accurately track the value of their assets and ensure that their financial statements are a true reflection of their financial performance.

The Matching Principle: Aligning Expenses with Long-Term Asset Usage

In the world of accounting, there’s a fundamental principle known as matching principle that plays a crucial role in ensuring accurate financial reporting. Simply put, this principle requires businesses to match expenses to the revenues they generate. It’s like a balancing act, where costs incurred are directly connected to the benefits they bring to the company.

When it comes to long-term assets, such as buildings, equipment, and intangible assets like patents, depreciation and amortization come into play. Depreciation is the process of spreading the cost of tangible assets over their useful life, while amortization does the same for intangible assets.

The matching principle dictates that these non-cash expenses should be recorded in the same period as the revenues they help generate. This allows businesses to present a more accurate picture of their financial performance, avoiding situations where expenses are recognized much later than the benefits they provided.

For example, if a company purchases a new piece of machinery that is expected to last for five years, the cost of that machinery is spread over the five-year period through depreciation. This means that a portion of the machinery’s cost is recorded as an expense in each of those five years, aligning the expense with the revenues that the machinery helps to generate.

Similarly, if a company acquires a patent that has a useful life of ten years, the cost of that patent is amortized over the ten-year period. This ensures that the expense is recognized in the same period as the benefits that the patent provides to the company.

By adhering to the matching principle, businesses can avoid the distortion of financial statements that can occur when expenses are not properly aligned with revenues. It’s like a jigsaw puzzle, where each piece needs to fit perfectly to create a complete and accurate picture of the company’s financial performance.

Capitalization vs. Expensing: A Critical Decision for Long-Term Asset Management

In the realm of accounting, the distinction between capitalizing and expensing is paramount when it comes to managing long-term assets. These non-current assets play a vital role in a company’s operations, and their classification can significantly impact financial statements and decision-making.

Capitalization refers to the practice of recognizing expenditures as assets, rather than expenses, on the balance sheet. This is typically done for items that are expected to provide long-term benefits to the company, such as buildings, machinery, or equipment. By capitalizing these costs, their value is spread out over the asset’s useful life, aligning with the matching principle of accounting. In other words, depreciation or amortization expenses are recognized gradually to match the revenue generated by the asset.

In contrast, expensing involves recognizing the entire cost of an asset as an expense immediately. This is typically done for assets with a short expected lifespan or that provide immediate benefits. The cost is deducted from revenue in the period in which it is incurred, significantly impacting the company’s income statement.

The decision between capitalization and expensing is not always straightforward and involves several factors, including:

- Materiality: Whether the asset’s value is significant enough to warrant capitalization.

- Benefits: Whether the asset is expected to generate future economic benefits that extend beyond the current period.

To summarize, capitalization and expensing are crucial accounting concepts that determine how long-term assets are recognized and recorded on financial statements. Capitalizing assets results in expenses being spread out over their useful life, while expensing recognizes the entire cost immediately. The appropriate choice between these options depends on the asset’s nature, its expected benefits, and its materiality.

Impairment: When Assets Lose Value

In the realm of accounting, assets are often held for extended periods, and their value can fluctuate over time. Impairment arises when the carrying value of an asset (its book value) exceeds its fair value (current market value). This scenario can occur due to various factors, such as technological advancements, changes in consumer preferences, or economic downturns.

When impairment is identified, businesses must recognize a loss on the income statement. This loss reflects the diminished value of the asset and helps to ensure that the financial statements accurately portray the company’s financial position. The impairment charge reduces the carrying value of the asset to match its fair value.

To determine if an asset is impaired, companies typically perform an impairment test. This test compares the carrying value to the fair value and evaluates any evidence of impairment. If impairment is suspected, the business may engage external appraisers or conduct internal assessments to determine the asset’s fair value.

Impairment can have significant implications for a company’s financial performance and decision-making. It can reduce reported earnings, lower asset values on the balance sheet, and affect tax liability. Therefore, businesses must carefully monitor their long-term assets for potential impairment and promptly address any identified impairments to maintain the integrity and accuracy of their financial statements.