Understanding The Behavioral Economics Approach: Challenging Rationality And Framing Effects

Traditional economists assume people are rational and seek to maximize utility. Behavioral economists challenge this view, recognizing the influence of emotions, cognitive biases, and social norms. They argue that individuals are boundedly rational, meaning they are subject to cognitive limitations and time constraints that affect decision-making. Behavioral economists also emphasize the importance of presentation of information, as framing affects choices.

**Traditional and Behavioral Economics: Divergent Perspectives on Human Behavior**

The world of economics has long been dominated by traditional economic theory, which assumes that individuals are rational actors who make decisions based on utility maximization. This theory views people as logical calculators, driven by self-interest. However, in recent decades, a challenger has emerged: behavioral economics. This approach recognizes that human behavior is often far from rational and is instead influenced by a host of emotions, cognitive biases, and social norms.

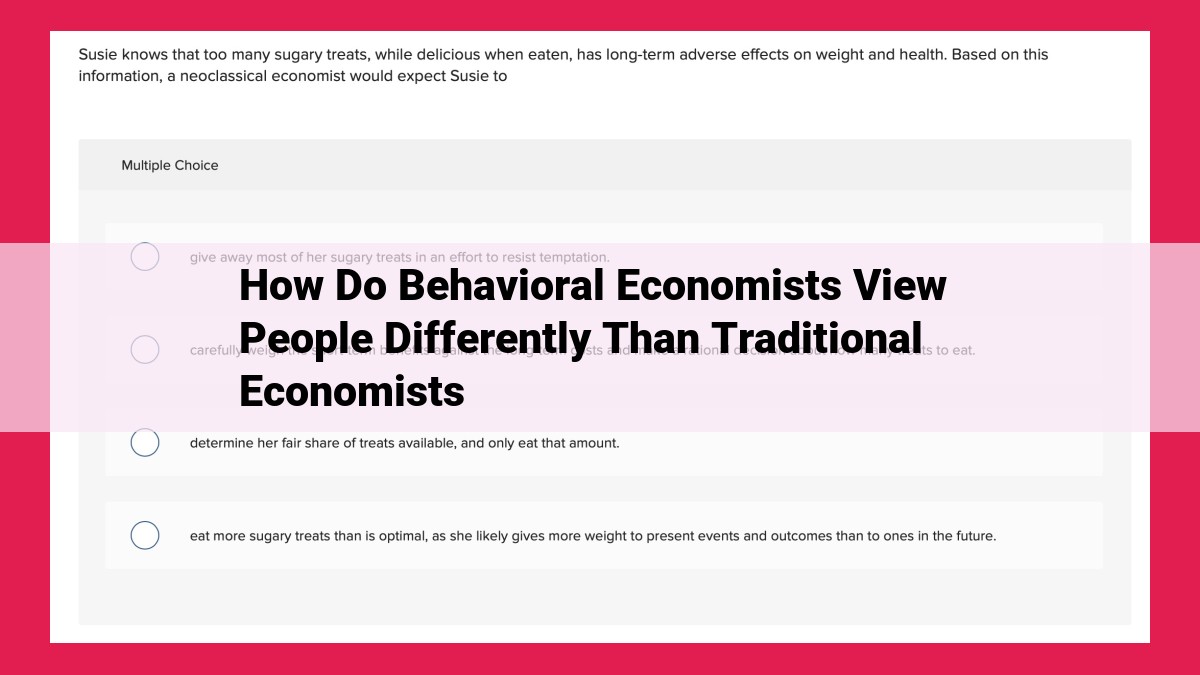

The fundamental difference between these two theories lies in their assumptions about human behavior. Traditional economics assumes that individuals are rational beings who weigh the costs and benefits of their decisions, acting in their best interests. Behavioral economics, on the other hand, acknowledges that humans are boundedly rational. This means that our cognitive limitations, or biases, and social influences can cloud our judgment and lead us to make decisions that may not be in our best interests.

This article explores the key differences between these two theories and examines how behavioral economics has revolutionized our understanding of human decision-making. By understanding the divergent perspectives of traditional and behavioral economics, we can gain a more nuanced appreciation of the complexities of human behavior and design better policies and interventions.

The Traditional Economic View: Rationality and Utility

In the realm of economics, the traditional perspective portrays humans as rational beings, driven by the pursuit of their well-being. This view, known as rationality, posits that individuals make decisions that aim to maximize their utility, a measure of their satisfaction or happiness.

Under this assumption, individuals are expected to be consistent in their preferences, meaning they will always choose the option that provides them with the highest level of utility. They are also expected to be forward-looking, weighing the potential costs and benefits of different choices over time to make optimal decisions.

This rational view has guided economic theories for decades, shaping policies and influencing market predictions. However, in recent years, behavioral economics has challenged these assumptions, highlighting the profound role of emotions, cognitive biases, and social factors in shaping our economic choices.

Unraveling the Behavioral Economic View: Emotions, Cognitive Biases, and Social Norms

Traditional economic theory has often relied on the assumption of rational behavior, where individuals make decisions based on logical calculations to maximize their utility. However, real-world observations have led to the emergence of behavioral economics, which recognizes that human decision-making is influenced by a myriad of factors beyond pure reason.

Behavioral economists acknowledge the profound role of emotions in our economic choices. Fear, hope, and greed can cloud our judgment, leading us to make impulsive purchases, panic sell investments, or take excessive risks. For instance, the fear of missing out (FOMO) can drive investors to make irrational investment decisions.

Furthermore, our decisions are often marred by cognitive biases, systematic errors in our thinking. Confirmation bias leads us to seek out information that confirms our existing beliefs, while ignoring contradictory evidence. Loss aversion makes us feel the pain of losing something more strongly than the pleasure of gaining something equivalent. These biases can distort our decision-making, leading to poor financial choices.

Social norms also shape our economic behavior. We are influenced by the expectations and behaviors of our peers, family, and society at large. For example, a strong cultural norm of saving may encourage individuals to prioritize saving over consumption, even if it means sacrificing their current well-being.

Recognizing the influence of emotions, cognitive biases, and social norms is crucial for understanding how people make economic decisions. This enhanced understanding can inform policymaking, improve financial literacy, and help individuals make more rational and informed choices.

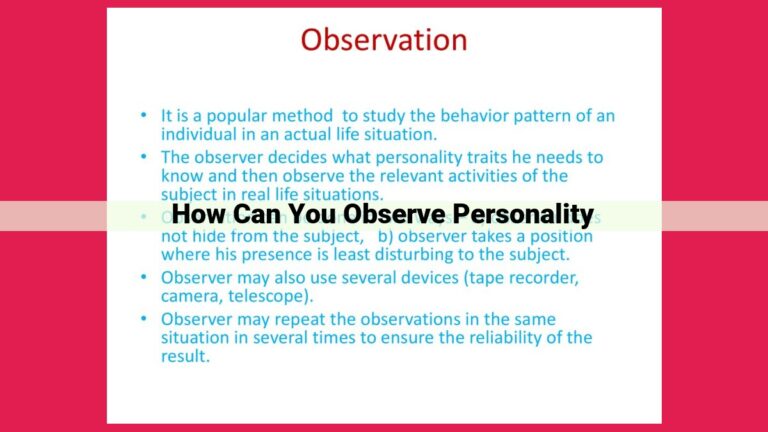

Bounded Rationality: Navigating Cognitive Limitations and Time Constraints

In the realm of economics, individuals are often portrayed as rational actors, making logical decisions to maximize their utility. However, the reality is that human decision-making is far more complex and imperfect. Bounded rationality acknowledges that individuals have cognitive limitations and time constraints which influence their choices.

Imagine yourself as a consumer faced with a plethora of choices. With limited time and cognitive bandwidth, it’s impossible to gather and process all available information to make the ideal decision. Instead, you rely on heuristics and mental shortcuts, which often lead to satisficing (finding a solution that is “good enough”) rather than optimizing (finding the best possible solution).

For example, when presented with a choice between two investment options, you may opt for the one with the higher returns without fully considering the associated risks. This is because evaluating all potential risks and returns would require significant time and effort, which you may not have.

Time constraints also play a significant role in bounded rationality. When faced with a deadline, you may hastily make decisions without due consideration, as you don’t have the luxury of extended deliberation. This can lead to impulsive purchases or suboptimal choices.

Implications for Economic Behavior

The concept of bounded rationality has profound implications for how we understand economic behavior:

- Imperfect Market Decisions: Individuals may not always make the most efficient choices in markets, leading to market inefficiencies and deviations from equilibrium.

- Policy Design: Policymakers must recognize the limitations of human rationality when designing policies to encourage desired behaviors. For instance, they could use nudges (subtle interventions designed to influence behavior) to guide people towards more rational decisions.

- Behavioral Finance: Bounded rationality explains anomalies in financial markets, such as irrational exuberance and herding behavior, as individuals make decisions influenced by emotions and cognitive biases.

Bounded rationality underscores the fact that human decision-making is not always rational or optimal. By understanding the constraints imposed by cognitive limitations and time pressures, economists can gain valuable insights into how individuals behave and make better predictions about economic outcomes. This knowledge can also inform the design of policies and interventions to promote more informed and efficient decision-making.

Framing: How Information Presentation Impacts Our Choices

In the realm of economics, behavioral economics has revolutionized our understanding of human decision-making by challenging the traditional notion that we are always rational actors. One key area where this deviation becomes apparent is in the framing of information.

Information presentation refers to how choices are presented to us. It plays a significant role in shaping our decisions, even when the underlying options remain the same. This phenomenon is eloquently captured in the following anecdote:

Imagine you’re offered a free gift. You can choose between a sure win of $20 or a 50% chance of winning $100. Most people would opt for the sure win. Now, consider a slight change in the framing: you now have a 50% chance of losing $20 or a 100% chance of keeping $80. Surprisingly, many people switch their preference to the latter option, even though it offers the exact same odds as before.

This seemingly paradoxical behavior highlights the power of framing. By changing the way the options are presented, we can influence individuals’ choices, even if the underlying outcomes are unchanged. This phenomenon is rooted in our cognitive biases, which can lead us to prioritize perceived losses or gains over objective values.

Cognitive biases are systematic errors in our thinking that can cloud our judgment. For instance, loss aversion refers to our tendency to weigh potential losses more heavily than equivalent gains. In the example above, the “loss” of $20 is framed more prominently than the potential gain of $80, leading many people to choose the seemingly safer option, even though it offers lower expected value.

Understanding the impact of framing is crucial for policymakers, marketers, and anyone who seeks to influence human behavior. By carefully considering how information is presented, we can design choices that nudge individuals towards desired outcomes without resorting to coercion or manipulation. This approach, known as nudging, has gained traction as a tool for promoting positive behaviors, such as healthy eating and saving for retirement.

In conclusion, the framing of information plays a pivotal role in shaping our choices. By acknowledging the influence of cognitive biases and understanding the power of presentation, we can make more informed decisions and design policies that effectively promote well-being.

Cognitive Biases: The Pitfalls of Irrational Decision-Making

In the realm of economics, the traditional perspective has long assumed that we’re all rational beings, making decisions that maximize our utility. However, behavioral economists have challenged this assumption, revealing the powerful influence of cognitive biases that lead us to make systematic errors and irrational decisions.

One common bias is confirmation bias. We tend to seek out information that confirms our existing beliefs and ignore evidence that contradicts them. This can lead to foolish choices, as we fail to consider all the relevant facts. For example, an investor who believes a particular stock will rise may only seek out positive news about the company, ignoring negative reports.

Another prevalent bias is loss aversion. We feel the pain of a loss more strongly than the pleasure of an equivalent gain. This can lead us to make irrational decisions, such as holding onto losing stocks out of a fear of realizing the loss. Imagine a gambler who continues betting despite losing streak, driven by the hope of winning back their losses.

Cognitive biases can have significant implications for our personal finances, investment decisions, and even our health. By understanding these biases, we can become aware of their potential pitfalls and make more informed and rational choices.

Social Norms: The Guiding Hands of Society

In the intricate tapestry of human behavior, social norms exert a profound influence on our decisions and actions. These unwritten codes of conduct, influenced by our social expectations, shape our interactions, shaping our behavior to conform with the accepted standards of our society.

The connection between social expectations and behavior is undeniable. We are constantly bombarded with cues and signals from our environment, informing us of what is considered appropriate and desirable. From the subtle nuances of body language to the explicit rules and regulations that govern our conduct, these expectations mold our choices.

For instance, in a formal setting like a business meeting, we instinctively adhere to certain norms, such as dressing professionally, maintaining eye contact, and speaking respectfully. These norms facilitate smooth interactions and create a sense of order.

In contrast, in more casual situations, such as social gatherings, different norms may apply. We may feel more at ease expressing our thoughts and opinions, and our behavior adapts accordingly.

Social norms not only influence our external behavior but also penetrate our cognitive processes. They shape our perceptions, preferences, and even our beliefs. We tend to adopt the values and opinions that are prevalent in our social groups, seeking approval and avoiding disapproval.

This phenomenon is particularly evident in decision-making. When faced with a choice, we often consider not only our personal preferences but also the social expectations that surround us. We may choose actions that align with what is considered right or acceptable, even if they conflict with our own desires.

Understanding the power of social norms is crucial for comprehending human behavior and designing effective policies. By leveraging these norms, policymakers and social engineers can nudge people towards desired behaviors and promote positive outcomes for society.

Nudges: A Gentle Push Towards Desired Behaviors

In the realm of behavioral economics, nudges have emerged as a subtle and influential tool for encouraging people to make wiser decisions. These gentle interventions aim to steer individuals towards desired behaviors without infringing upon their freedom of choice.

Behavior change refers to interventions that influence people’s choices, even if it deviates from their initial preferences or habitual behaviors. Nudges are designed to nudge people in the direction of behaviors that are beneficial to themselves or society, such as promoting healthy eating, saving for retirement, or reducing energy consumption.

Paternalism is a concept that raises ethical concerns about nudges. It questions whether it is ethical for policymakers or other authorities to intervene in people’s choices, even with the intention of promoting their well-being. However, proponents of nudges argue that they can be justified when the benefits to individuals and society outweigh the potential infringements on autonomy.

Nudges can take various forms. One common approach is Framing, which involves presenting information in a way that highlights the benefits of a particular choice. For example, instead of phrasing a message as “Don’t smoke,” it could be framed as “Protect your loved ones from secondhand smoke.”

Another technique is ** Defaults**. By setting up default options that align with desired behaviors, nudges can make it easier for people to choose the healthier or more sustainable option. For instance, automatically enrolling individuals in a retirement savings plan increases the likelihood of saving for the future.

Social pressure can also be harnessed as a nudge. Displaying information about the choices of others, such as the percentage of people who have made a particular choice, can influence individuals to conform to the social norm.

Nudges have gained popularity in public policy as a cost-effective and effective way to promote positive behavior change. They have been successfully implemented in areas such as healthcare, education, and environmental conservation. By leveraging insights from behavioral economics, policymakers can design nudges that encourage people to make choices that are beneficial to both themselves and society.