Unlock The Elements Of Poetry: Analyze Structure, Meaning, And Impact

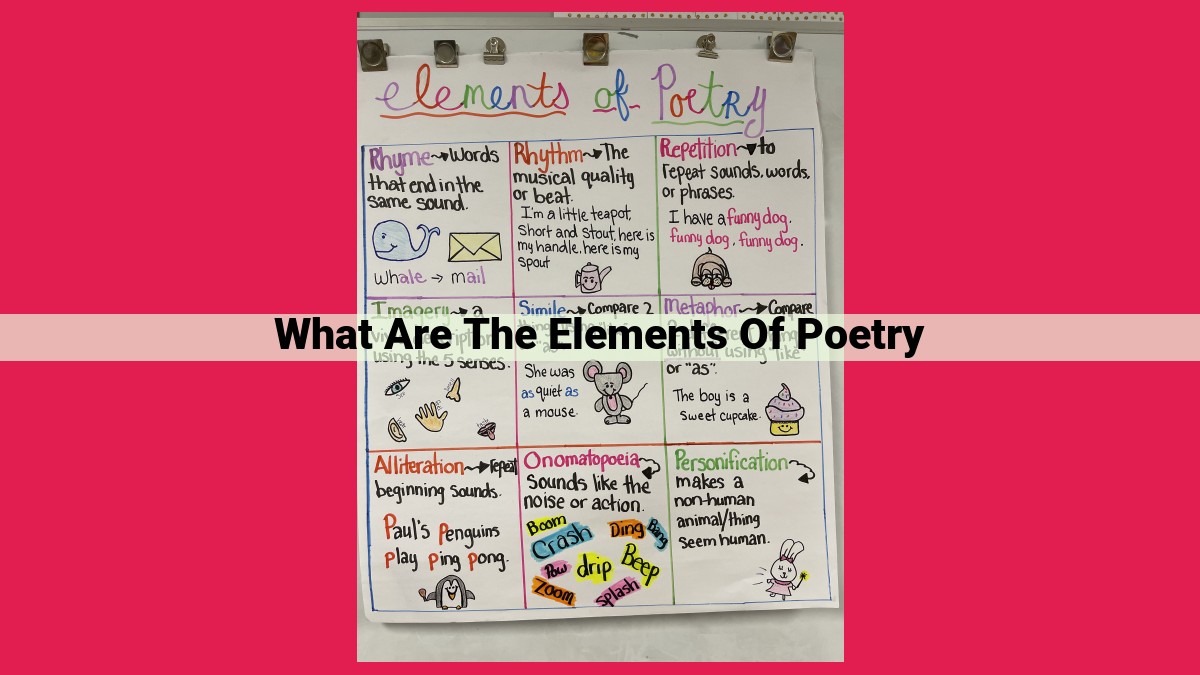

Poetry’s elements form the backbone of its structure, meaning, and impact. These include theme (the poem’s central idea), voice (the speaker’s perspective), form (structure and shape), imagery (sensory language), symbolism (objects and ideas with deeper meanings), figurative language (comparisons and devices), sound devices (enhancements to auditory experience), rhythm (flow and timing), and meter (specific patterns of stressed and unstressed syllables). Understanding these elements empowers readers to delve into the depth of poetic expression.

Theme: The Heart of the Poem

In the realm of poetry, the theme reigns supreme as the very essence of the piece. It’s the soul that breathes life into the words, conveying a profound message that resonates with readers. The theme is the central idea around which all other elements of the poem revolve, giving it purpose and meaning.

Just like a leitmotif in music, a theme runs through a poem, binding its stanzas together like a silken thread. It’s not merely a subject matter but rather a deeper truth that the poet seeks to impart. It can be a universal concept like love or loss or something more abstract, like the beauty of nature or the fragility of life.

Identifying the theme of a poem is crucial for understanding its inner workings. It’s the key that unlocks the door to the poet’s heart and allows us to participate in the journey they’re inviting us on. By exploring the theme, we uncover the poet’s perspective on the world and the experiences that shaped their words.

Voice: The Messenger’s Perspective

In the realm of poetry, voice emerges as a crucial element that breathes life into the written words. It acts as the conduit through which the poet’s thoughts, emotions, and stories are conveyed to the reader. The speaker, or the voice that narrates the poem, assumes a pivotal role in shaping the reader’s interpretation and experience.

Persona vs. Narrator: Unveiling the Speaker’s Identity

The speaker in a poem can adopt different identities, each serving a specific purpose. One common distinction is between the persona and the narrator. A persona is a carefully crafted character created by the poet to deliver the message, while a narrator is a more objective observer or storyteller.

Understanding the differences between these two roles is essential for comprehending the poem’s perspective. The persona’s thoughts and feelings may not necessarily align with those of the poet, whereas the narrator typically maintains a more detached stance, relaying events and experiences as they unfold.

The Speaker’s Impact on the Poem’s Meaning

The speaker’s voice can significantly alter the poem’s meaning and impact. A persona can create a specific emotional connection with the reader, allowing them to immerse themselves in the character’s experiences. For example, in Sylvia Plath’s “Daddy,” the persona’s raw and confessional voice amplifies the poem’s themes of trauma and loss.

On the other hand, a narrator can provide a more analytical or distant perspective, inviting the reader to critically examine the events and ideas presented in the poem. In T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” the impersonal narrator’s fragmented observations mirror the poem’s exploration of modern society’s alienation and fragmentation.

Exploring the Spectrum of Voices

Poets employ a vast array of voices to convey their messages, each contributing unique nuances to the poem’s overall meaning. From the first-person narrator who shares their personal experiences to the third-person observer who witnesses the events unfold, the speaker’s voice serves as a versatile tool to engage, provoke, and inspire the reader.

Form: The Framework of Poetry

Poetry is not merely a collection of words strung together; it’s a meticulously crafted structure that shapes its meaning and impact. The form of a poem encompasses the arrangement of stanzas, verses, and rhyme scheme. These elements provide the backbone of the poem, influencing its rhythm, flow, and overall shape.

Stanzas and Verses: The Building Blocks

Stanzas are units of lines grouped together, like paragraphs in prose. They can vary in length and form, creating distinct sections within the poem. Verses, on the other hand, are individual lines of poetry that contribute to the stanza and the poem as a whole.

Rhyme Scheme: The Music of Words

Rhyme scheme refers to the pattern of rhyming words within a poem. It can be consistent (AABB), alternate (ABAB), or irregular. Rhyme scheme adds a melodious element to poetry, enhancing its musicality and making it more memorable.

Impact of Form

The form of a poem is not just a technicality; it plays a significant role in shaping the poem’s message and impact. For example, sonnets, with their strict form of 14 lines and specific rhyme scheme, are often used to explore themes of love, beauty, and mortality. Free verse, on the other hand, with its lack of formal constraints, allows poets to experiment with language and create more personal and introspective works.

By understanding the form of poetry, we can appreciate the craft and artistry that goes into its creation. It’s like unraveling a secret code, revealing the hidden structures that give poetry its power and resonance.

Imagery: Painting with Words

- Define imagery as the use of sensory language to create vivid pictures.

- Discuss related concepts such as sensory language and figurative language.

Imagery: Painting with Words

In the realm of poetry, words become vivid brushstrokes that paint breathtaking images upon the canvas of our imaginations. This is the essence of imagery, the art of using sensory language to create striking and evocative pictures.

The Power of Sensory Language

Imagery draws its power from sensory language, words that appeal to our senses. Through sight, sound, smell, taste, and touch, imagery transports us into the poem’s world, allowing us to experience it through multiple perspectives.

Figurative Language: Imagery’s Companion

Imagery often intertwines with figurative language, such as metaphors, similes, and personification. These devices compare, contrast, and personify objects or ideas, creating unexpected and imaginative connections.

Types of Imagery

- Visual Imagery: Paints images in our minds, evoking vivid scenes, characters, and objects.

- Auditory Imagery: Captures sounds, from the whisper of the wind to the roar of the ocean.

- Tactile Imagery: Lets us feel the textures, temperatures, and sensations of the poem’s world.

- Olfactory Imagery: Transports us through scents, whether they be sweet, pungent, or evocative.

- Gustatory Imagery: Tantalizes our taste buds with descriptions of flavors, textures, and aromas.

Impact of Imagery

Effective imagery immerses the reader in the poem’s world, making it more engaging, memorable, and emotionally resonant. It can:

- Elevate the poem’s language: Imagery replaces abstract concepts with concrete and vivid experiences.

- Create vivid impressions: Sensory details etch the poem’s scenes and characters into our minds.

- Evoke emotions: Imagery triggers emotional responses by appealing to our senses and memories.

Crafting Effective Imagery

To craft impactful imagery, poets:

- Use specific and concrete language: Avoid vague or generic terms; instead, use words that create clear mental pictures.

- Engage multiple senses: Appeal to as many senses as possible to create a multi-sensory experience.

- Experiment with figurative language: Metaphors, similes, and personification can add depth, surprise, and creativity to imagery.

Symbolism: Unlocking Poetry’s Hidden Depths

In the realm of poetry, symbols reign supreme, transforming mere words into powerful representations of abstract ideas and emotions. They are like enigmatic keys that unlock the hidden depths of a poem, inviting us on an enchanting journey of discovery.

Definition and Types: Symbols and Their Guises

Symbolism is the art of using objects, images, or ideas to represent something beyond their literal meaning. These symbolic elements can take various forms:

- Metaphors: When two seemingly unrelated things are directly compared, revealing a deeper connection.

- Allegories: Extended metaphors that weave a fictional tale to convey a moral or religious truth.

- Personifications: When human qualities are attributed to non-human entities, breathing life and emotion into inanimate objects.

Impact and Interpretation: Symbols as Bridges to Meaning

Symbols are more than mere linguistic curiosities; they serve as bridges to deeper meaning. By understanding their contextual significance, we can uncover the poet’s intended message and appreciate the poem’s emotional resonance.

For instance, in Emily Dickinson’s iconic poem, “Hope” is personified as a small bird that “sings at dawn.” This vivid imagery transcends the literal description of a bird, suggesting resilience and optimism in the face of adversity.

Poetic Impact: Symbols as Tools of Expression

Symbols are not merely decorative flourishes in poetry; they are essential tools of expression. They allow poets to:

- Condense Complex Ideas: Symbolize abstract concepts in a tangible and evocative form.

- Evoke Emotions: Tap into our emotions through resonant imagery and associations.

- Create Ambiguity: Introduce multiple interpretations, inviting readers to engage intellectually with the poem.

Symbolism is the lifeblood of poetry, infusing it with depth, meaning, and emotional power. By understanding the art of symbolism, we can unlock the hidden secrets that lie beneath the surface of poetic language. It is a journey of discovery, where every symbol we encounter becomes a key to a new world of understanding.

Figurative Language: Unveiling the Power of Words

Figurative language is the magic wand that transforms ordinary words into enchanting expressions, lending poetry and literature their captivating charm. These non-literal comparisons paint vivid pictures, evoke emotions, and sharpen our perception of the world.

When poets employ a simile, they draw parallels between two seemingly disparate entities using “like” or “as.” In Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 18,” the beloved’s eyes are likened to “the sun’s gold,” evoking a sense of radiant beauty and warmth.

Alliteration, the repetition of initial consonant sounds, creates a harmonious rhythm that draws attention to specific words. In Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven,” the haunting repetition of “nevermore” lingers in the reader’s mind, emphasizing the bird’s ominous prophecy.

Hyperbole, an exaggeration for effect, captures extreme emotions or ideas with comic or dramatic flair. Mark Twain quipped, “I’ve been through more reincarnations than a circus clown.” This humorous exaggeration underscores the writer’s extensive life experiences.

Other types of figurative language include metaphors, allegories, and personifications. A metaphor directly equates two things, revealing their intrinsic similarities. In William Blake’s “The Tyger,” the animal is depicted as “burning bright” like fire, symbolizing both its power and the awe it inspires.

Allegories tell a surface-level story that also symbolizes a deeper, often moral message. George Orwell’s “Animal Farm” uses the lives of animals to satirize the dangers of totalitarianism.

Personification imbues inanimate objects or abstract concepts with human qualities. In John Keats’s “Ode to a Nightingale,” the bird’s song is personified as a “plaintive anthem,” capturing its melancholic beauty.

Figurative language is not merely an embellishment; it is a powerful tool that poets use to deepen meaning, arouse emotions, and create lasting impressions in the reader’s mind. By skillfully wielding these linguistic devices, poets invite us to see the world anew, igniting our imagination and expanding the boundaries of our understanding.

Sound Devices: The Music of Words

When we read a poem, we’re not just absorbing its meaning, but also its sound. Poets carefully craft their words to create a symphony of language that dances across our ears, evoking emotions and amplifying the impact of their message.

Sound devices are a powerful tool in a poet’s arsenal. They enhance the auditory experience of poetry, making it not just a reading exercise but a sensory journey. Onomatopoeia, assonance, and consonance are three common sound devices that bring poems to life.

Onomatopoeia is a fun and playful way to bring a poem to life. By using words that sound like the actions they describe, onomatopoeia provides an instant, visceral connection between the written word and the reader’s imagination. Think of buzz, splash, or screech—words that paint a vivid sonic picture in our minds.

Assonance and consonance work their magic by repeating vowel and consonant sounds, respectively. These repetitions create a musical flow that enhances the poem’s rhythm and melody. In assonance, vowels take center stage: long, tall, and dawn dance in a harmonious chorus. Consonance, on the other hand, focuses on consonant sounds, creating a percussive effect that adds depth and texture to the poem.

These sound devices are not just cosmetic enhancements. They serve a deeper purpose by amplifying the poem’s message. Onomatopoeia can underscore an action’s significance, while assonance and consonance can create an emotional atmosphere.

In William Wordsworth’s “Ode to a Nightingale,” the poet uses assonance to evoke a sense of tranquility and timelessness:

“My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk…”

The repetition of the long “a” vowel sound creates a soothing and hypnotic effect, immersing the reader in the poem’s dreamy atmosphere.

Sound devices are the hidden musicians in the orchestra of poetry. They work seamlessly with other elements—theme, imagery, figurative language—to create a multisensory experience that resonates deep within us. Embrace their magic, and let the music of words transport you to realms of wonder and enchantment.

Rhythm: Timing and Flow

Rhythm, the heartbeat of poetry, is the rhythmic pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables that gives verse its musicality. It’s the subtle pulse that guides our reading, adding a layer of emotion and expressiveness to the words.

Cadence, tempo, and beat are the three pillars that support rhythm. Cadence refers to the natural flow of the words, the way the lines pause and accelerate, creating a sense of momentum. Tempo dictates the speed at which the poem is read, influencing the overall mood and atmosphere. Beat, on the other hand, is the underlying rhythmic unit that governs the placement of stresses and unstresses.

By manipulating these elements, poets can create a symphony of sounds that enhances the meaning of their words. A fast and furious beat, for instance, can evoke a sense of urgency and excitement, while a slow and measured pace imparts a sense of serenity or contemplation.

The choice of meter, a specific pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables, further contributes to the poem’s rhythm. Iambic pentameter, with its alternating pattern of unstressed and stressed syllables, has been a favorite of poets for centuries, providing a stately and dignified tone. Trochaic octameter, on the other hand, with its alternating pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables, creates a more energetic and lively rhythm.

By understanding the power of rhythm, poets can craft verses that resonate with our senses and emotions, transforming words into a captivating musical experience.

Meter: Rhythm’s Guiding Hand

In the realm of poetry, meter reigns supreme as the rhythmic heartbeat that drives the melodic flow of words. It is the structured dance of stressed and unstressed syllables, shaping the musicality and cadence that captivates readers and listeners alike.

Unveiling the Essence of Meter

Meter is the underlying pattern that governs the arrangement of stressed and unstressed syllables within a line of poetry. Stress refers to the emphasis or weight given to certain syllables, creating a rhythmic pulse. Unstressed syllables, on the other hand, provide a backdrop against which the stressed syllables shine.

Common Types of Meter

The world of poetry boasts a rich tapestry of metrical patterns, each imparting its own distinctive rhythm and feel. Let’s explore some of the most prevalent types:

- Iambic Meter: A graceful rhythm characterized by alternating unstressed and stressed syllables, like a gentle heartbeat: “The curfew tolls the knell of parting day.”

- Trochaic Meter: A marching rhythm with stressed syllables followed by unstressed ones, evoking a sense of purpose and determination: “Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary.”

- Spondaic Meter: A powerful rhythm consisting solely of two stressed syllables, conveying a weighty or emphatic tone: “Break, break, break.”

Meter’s Impact on Poetry

Meter plays a pivotal role in shaping the overall impact of a poem. It can enhance emotional expression, create a sense of continuity or contrast, and influence the pace and flow of the words. A well-chosen meter can amplify a poem’s message, leaving a profound and lasting impression on the reader.