Understanding Poetic Line Structure: Meter, Rhythm, And Enjambment

A line of poetry, a fundamental unit of poetic structure, is a single, unbroken line of verse. Types of verse lines include regular lines and stanzas, groups of lines. Enjambment creates flow by carrying a thought across multiple lines, while caesura is a mid-line pause that influences rhythm and structure. Poetic feet, building blocks of rhythm, are composed of stressed and unstressed syllables. Meter, a rhythmic pattern, is determined by the arrangement of feet. Analyzing a poem’s line structure through scanning reveals its rhythmic framework.

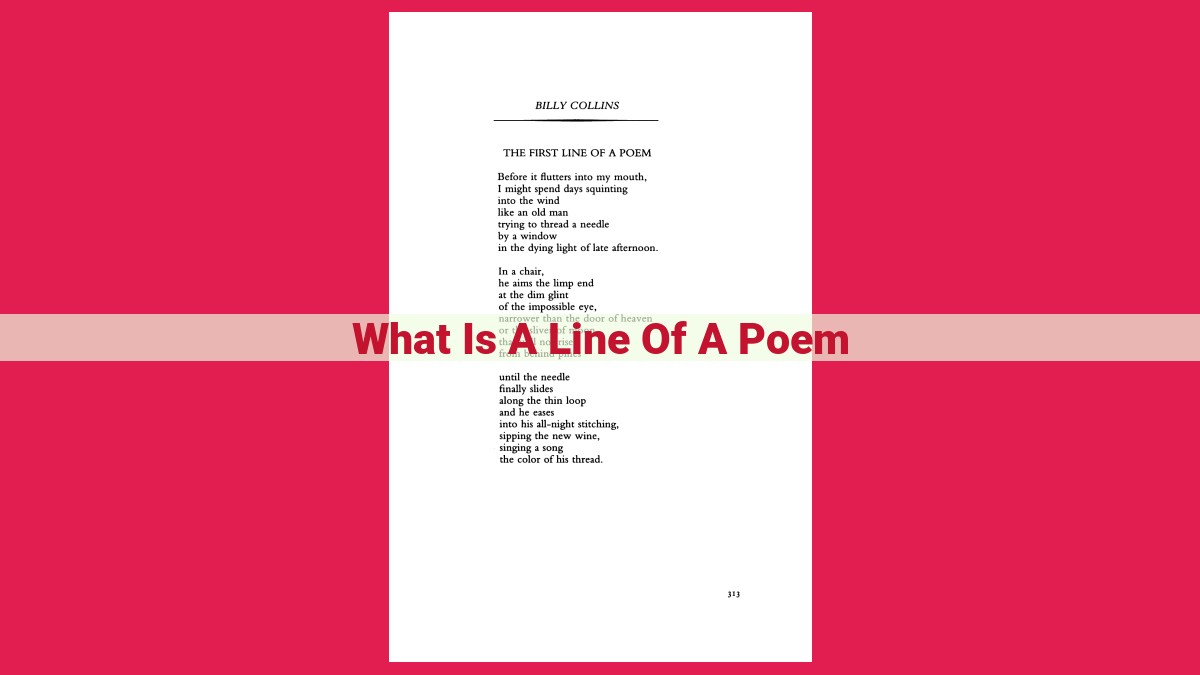

Understanding the Line in Poetry: A Poetic Journey

At its heart, poetry is a dance of words, a harmonious blend of rhythm and meaning. The line, the fundamental unit of poetic structure, is the building block that shapes this dance. It is within the confines of these lines that poets create magic, weaving words that resonate with our hearts and minds.

The Definition and Significance of the Poetic Line

A line of poetry is not merely a collection of words; it is a living, breathing entity, a vessel for rhythm and expression. It can be a single, unbroken thought, or a series of smaller units that flow into each other, creating a tapestry of meaning. Lines provide structure to the poem, guiding the reader’s eye and ear through the poetic landscape.

The Unbroken Line: Verse Line and Stanza

The simplest form of a poetic line is the verse line, a standalone unit of rhythm and imagery. When several lines come together, they form a stanza, a larger unit that often explores a specific aspect or theme within the poem. The interplay between verse line and stanza creates a rhythmic foundation, building anticipation and guiding the reader’s interpretation.

Enjambment and the Unending Flow

Enjambment, the technique of running a sentence or phrase across multiple lines, adds a sense of fluidity to the poem. It creates a seamless transition, allowing the poet to extend ideas beyond the confines of a single line. Enjambment forces the reader to slow down, savoring the flow of words and connecting the dots of meaning.

Caesura: The Pause that Refreshes

Sometimes, a line of poetry demands a moment of reflection, a brief pause to emphasize a particular thought or emotion. This pause, known as a caesura, divides the line into two sections. Caesuras create a rhythmic tension, giving the reader time to absorb the significance of the words that have come before and anticipate what is to come.

Poetic Feet: The Rhythmic Building Blocks

The rhythm of a poem is built upon the foundation of poetic feet, the repeating units of stressed and unstressed syllables. Common poetic feet include the iamb (an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable) and the trochee (a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed syllable). The arrangement of these feet within a line creates a distinctive rhythmic pattern, adding a musicality to the words.

Meter: The Rhythmic Pattern

The repetition of poetic feet leads to the creation of meter, a consistent rhythmic pattern that runs throughout the poem. Popular meters include iambic pentameter, with its five iambic feet per line, and trochaic octameter, with its eight trochaic feet per line. Meter adds a sense of order and predictability to the poem’s rhythm, enhancing its memorability and impact.

Scanning: Unveiling the Rhythmic Structure

To truly appreciate the rhythmic intricacies of a poem, one must engage in the art of scanning. Scanning involves identifying the poetic feet and counting the stressed and unstressed syllables to determine the poem’s meter. This process unveils the underlying rhythmic architecture, revealing the poet’s craftsmanship and the poem’s musicality.

Types of Verse Lines

The arrangement of words into lines is a fundamental aspect of poetry, giving shape and structure to the poetic expression. Verse lines can be broadly categorized into two primary types:

Verse Line

A verse line stands alone as a single, unbroken line of poetry. It is the most basic unit of line structure, representing a complete thought or image. Verse lines can vary greatly in length and rhythm, contributing to the overall flow and tone of the poem. For example, in William Carlos Williams’ famous poem “The Red Wheelbarrow,” each line is a distinct verse line:

so much depends

upon

a red wheel

barrow

glazed with rain

water

beside the white

chickens

Stanza

A stanza is a group of verse lines that are separated by a blank line. Stanzas provide a larger structural unit within the poem, often used to develop a particular theme or idea. Stanzas can vary in length and form, creating different effects on the reader’s experience. For example, in John Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale,” the poem is composed of eight stanzas, each presenting a different aspect of the speaker’s encounter with the nightingale:

My heart aches, and a drowsy numbness pains

My sense, as though of hemlock I had drunk,

Or emptied some dull opiate to the drains

One minute past, and Lethe-wards had sunk:

'Tis not through envy of thy happy lot,

But being too happy in thine happiness,—

That thou, light-winged Dryad of the trees,

In some melodious plot

Of beechen green, and shadows numberless,

Singest of summer in full-throated ease.

The distinction between verse lines and stanzas lies in their relationship to each other. Verse lines are individual units, while stanzas are groups of verse lines. The arrangement of lines into stanzas provides additional structure and organization to the poem, allowing for the development of themes and ideas over multiple lines.

Enjambment: The Art of Broken Lines

In the realm of poetry, where words dance and meaning unfolds, the line is a fundamental unit, shaping the rhythm, flow, and impact of a poem. Enjambment, a technique that breaks a sentence across multiple lines, plays a crucial role in crafting the poetic experience.

Unveiling Enjambment’s Essence

Enjambment, derived from the French term “enjamber” (to stride across), occurs when a sentence continues from one line to the next without a natural pause or punctuation. This creates a sense of movement and continuity, drawing the reader through the poem with an uninterrupted flow of ideas.

Harnessing the Power of Enjambment

Poets wield enjambment as a powerful tool to:

- Create Smooth Transitions: By breaking lines at strategic points, enjambment helps connect ideas smoothly, allowing them to flow into one another seamlessly.

- Build Tension and Suspense: When a sentence is abruptly cut off at the end of a line, it leaves the reader in a state of anticipation and curiosity. This technique heightens the impact of the following lines, creating a sense of suspense or excitement.

- Convey Hidden Meanings: Enjambment can also be used to suggest deeper connections between words and phrases. By juxtaposing words across lines, poets can create unexpected associations and invite readers to explore multiple layers of meaning.

Guiding the Reader’s Journey

Enjambment acts as a subtle guide, leading the reader along the poetic path:

- Directing Attention: Poets use enjambment to emphasize certain words or phrases by placing them at the beginning or end of a line. This technique draws the reader’s attention and encourages them to focus on specific elements of the poem.

- Creating Rhythm and Pace: The interplay of unbroken lines and line breaks creates a unique rhythm and pace within the poem. Enjambment can slow down the reading process or accelerate it, depending on the length and frequency of the line breaks.

- Enhancing Emotional Impact: By breaking sentences at emotionally charged moments, poets can intensify the reader’s emotional response. This technique allows feelings to linger and reverberate across multiple lines.

Caesura: The Power of the Mid-Line Pause

In the tapestry of poetry, the line stands as a fundamental thread, weaving together words and rhythms. Within this poetic canvas, the caesura emerges as a vital element, a mid-line pause that pauses the flow and imparts a rhythmic interlude.

Imagine a dancer pirouetting across the stage, a graceful pause in their movement that accentuates the beauty of their form. Similarly, in poetry, a caesura serves as a strategic break, allowing the reader to savor the weight and cadence of each line. It creates a moment of reflection, a pause that allows the rhythm to breathe.

Beyond its rhythmic implications, the caesura also plays a pivotal role in shaping the structure of the poem. By dividing the line into two distinct segments, it creates a sense of balance and symmetry. It can emphasize certain words or phrases, drawing attention to their importance within the poetic tapestry.

Furthermore, the placement of the caesura can influence the mood and tone of the poem. A caesura in the middle of the line can create a sense of stability and equilibrium, while one placed near the end can lend a sense of anticipation or suspense.

In essence, the caesura is a powerful tool in the poet’s arsenal, allowing them to craft intricate rhythms, shape the structure of the poem, and convey a range of emotions and ideas. It is an integral part of the poetic line, adding depth and nuance to the written word.

Feet: The Building Blocks of Rhythmic Poetry

In the realm of poetry, words dance to a hidden beat, a rhythm that weaves its way through the lines and verses. The secret to this captivating melody lies in the intricate construction of poetic feet, the fundamental units of rhythm in verse.

Imagine each poetic foot as a miniature musical measure, consisting of a specific arrangement of stressed and unstressed syllables. Like the notes in a song, these rhythmic patterns create a cadence that guides the reader’s ear through the poem’s soundscape.

The iamb, a dance of two syllables, is a common poetic foot. Its rhythm da DUM echoes the heartbeat, making it a natural fit for narrative poems and lyrical verse. The trochee, on the other hand, inverts the iamb, stepping to a DUM da rhythm. This forceful stride lends itself well to poetry that conveys energy, movement, or excitement.

The combination and repetition of poetic feet create meters, the larger rhythmic patterns that shape the poem’s overall sound. Iambic pentameter, a cadence of five iambs, is a classic example, often employed in sonnets and dramatic poetry. Trochaic octameter, with its eight trochaic feet, reverberates with a marching beat, ideal for epic poems and heroic narratives.

By understanding the formation and function of poetic feet, we unlock the secrets of the poem’s rhythm. Rhythm becomes more than just an acoustic feature; it serves as a storytelling device, guiding our emotions, intensifying the drama, and shaping the meaning of the words it carries.

Meter: The Rhythmic Pattern in Poetry

Dive into the fascinating world of poetry and discover the intricacies of meter, a fundamental element that weaves a rhythmic tapestry within the lines. Meter, like a musical score, dictates the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables, creating a harmonious cadence that guides the reader through the poem’s emotional landscape.

Every foot, a poetic building block, consists of a specific combination of stressed and unstressed syllables. Iambs, for instance, gracefully alternate between unstressed and stressed syllables, creating a graceful and flowing rhythm. Trochees, on the other hand, reverse this pattern, with a stressed syllable followed by an unstressed one, imparting a sense of power and energy.

As these feet come together, they form a rhythmic pattern known as meter. Iambic pentameter, a prevalent meter in English poetry, consists of five iambs in a line, creating a graceful and stately cadence. Trochaic octameter, with its eight trochaic feet, conveys a powerful and dramatic rhythm.

Understanding meter is akin to deciphering a musical composition. By scanning the poem, identifying stressed and unstressed syllables, we unravel the rhythmic structure that underlies the poet’s words. This intricate dance of meter shapes the poem’s tone, mood, and emotional impact.

In “The Raven” by Edgar Allan Poe, the haunting rhythm of trochaic octameter mirrors the speaker’s despair and obsession:

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary

Each line’s eight trochaic feet create a steady, relentless beat, evoking the speaker’s restless mind and the oppressive atmosphere of the poem.

Contrastingly, in Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s “Sonnet 43,” the iambic pentameter conveys a sense of longing and vulnerability:

How do I love thee? Let me count the ways.

The alternating pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables creates a lyrical flow that mimics the speaker’s tender emotions and the depth of their love.

Understanding poetry’s rhythmic patterns is like gaining a secret key to the poet’s mind. It allows us to discern the subtle nuances of emotion, tone, and imagery conveyed through the skillful arrangement of words in poetic lines.

Scanning: Unveiling the Rhythmic Heartbeat of Poetry

Poetry is a symphony of words, where rhythm plays a pivotal role in creating its mesmerizing cadence. Lines, the essential building blocks of poetic structure, hold the secrets to this rhythmic tapestry. Understanding the art of scanning is like deciphering a musical score, revealing the intricate patterns that give poetry its heartbeat.

Scanning involves analyzing each line, identifying the feet—groups of syllables that form the rhythmic units. By identifying the stressed and unstressed syllables within each foot, we can discern the poem’s meter, the underlying rhythmic pattern. This process is like dissecting a melody, breaking it down into its constituent notes and rhythms.

The importance of scanning cannot be overstated. It allows us to penetrate the poem’s rhythmic structure, unlocking its innermost workings. It’s like having an X-ray vision into the poet’s mind, understanding the calculated choices they made to craft their verbal masterpiece. By scanning, we gain insights into the poem’s flow, its emotional undertones, and its intended impact on the reader.

So, grab your poetic magnifying glass and embark on a journey into the rhythmic realm of poetry. Let’s listen attentively to the heartbeat of the lines, unraveling the secrets that lie within their measured dance.