Understanding Good Measure: Achieving Balance And Appropriateness

Good measure refers to an adequate or appropriate amount of something, avoiding extremes. It balances sufficiency, abundance, and moderation, considering context and subjective/objective perspectives.

What Does Good Measure Mean?

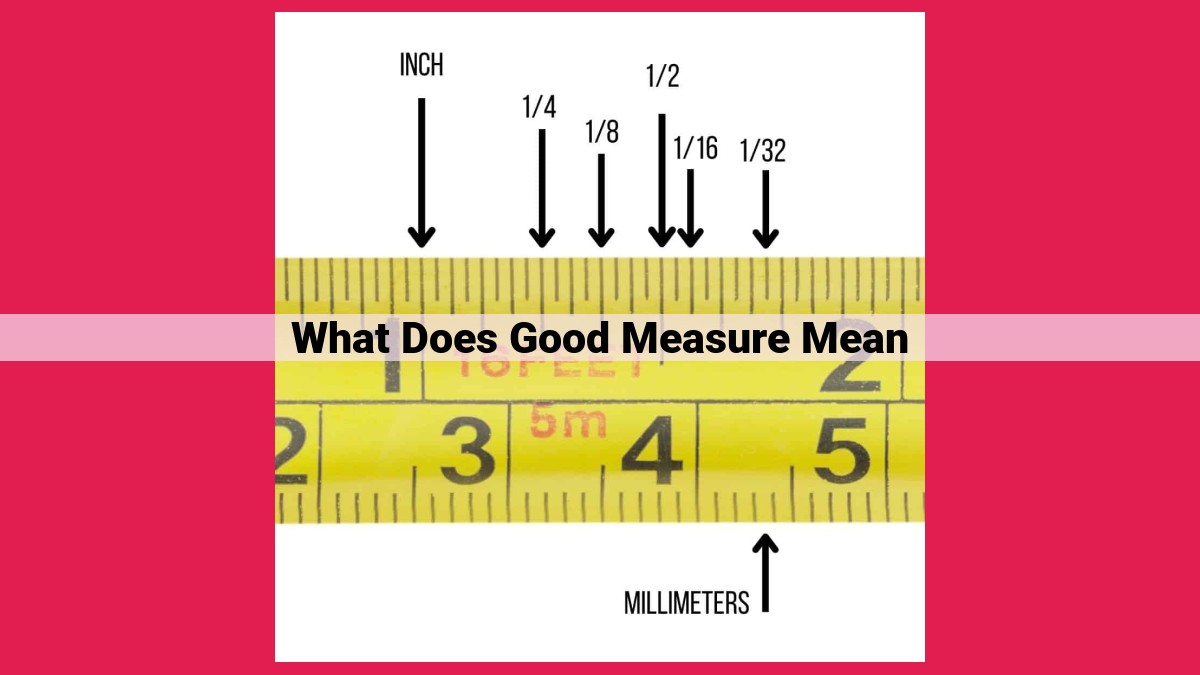

Understanding Standard Measurements

Good measure encompasses a range of concepts related to quantity. Adequacy refers to a sufficient amount, meeting necessary requirements. Abundance, on the other hand, signifies an excessive quantity beyond what is typically needed. Moderation emphasizes the avoidance of extremes, finding the middle ground between excessive and deficient. Conversely, excess describes a surplus that exceeds what is necessary, often leading to negative consequences. Deficiency represents a lack or shortage, leaving a need unmet.

Adequate Measure: Balancing Sufficiency and Excess

An adequate measure is one that balances sufficiency with moderation. It considers the context and purpose of the measurement, ensuring that there is enough to meet the need but not so much as to create waste or imbalance. Adequacy is not a stagnant concept but rather a dynamic balance that can vary depending on the circumstances.

Abundance: The Double-Edged Sword of Plenty

While having more than enough may seem desirable, abundance can also pose challenges. Excessive quantities can lead to waste, depletion of resources, and even negative environmental impacts. It’s important to balance abundance with moderation, recognizing that having too much can sometimes be as detrimental as having too little.

Moderation: Seeking the Golden Mean

Finding the golden mean between extremes is crucial for achieving good measure. Moderation involves avoiding both excess and deficiency, striking a balance that promotes harmony and equilibrium. It requires careful consideration of context, appropriateness, and the consequences of actions.

Excess and Deficiency: Unhealthy Extremes

Excess and deficiency represent the unhealthy extremes of measurement. Excess can result in waste, imbalance, and potential harm. Deficiency, on the other hand, can lead to unfulfilled needs, setbacks, and limitations. Understanding the consequences of both excesses and deficiencies is essential for making sound decisions.

Adequate Measure: Striking the Delicate Balance

An adequate measure is a quantifiable amount that fulfills a specific need or purpose. It is the optimal quantity that avoids extremes while ensuring sufficiency.

Sufficiency, Abundance, Moderation, and Context:

To define an adequate measure, one must consider its sufficiency, abundance, moderation, and context. Sufficiency ensures that the amount is enough to meet the intended purpose, while abundance warns against excessive quantities. Moderation strikes a balance between excess and deficiency. The context in which the measure is applied plays a crucial role in determining its adequacy.

Abundance: The Implications of Excess

Adequacy, sufficiency, and balance: These terms are closely intertwined with abundance. Adequacy suggests that a certain quantity is sufficient for a particular purpose, while sufficiency implies there is enough to meet a need or requirement. Balance, on the other hand, refers to a state of equilibrium or harmony among different elements or qualities.

Excess occurs when there is more than what is deemed adequate or sufficient. While abundance may evoke images of wealth and plenty, it can also lead to imbalance and negative consequences.

The Implications of Excess

Abundance can have both positive and negative implications. On the one hand, it can allow for greater freedom, choice, and opportunities. For example, an abundance of food can provide nourishment and sustenance, while an abundance of resources can facilitate technological advancements and economic growth.

On the other hand, excess can also lead to wastefulness, inefficiency, and even negative health effects. An abundance of food can result in overconsumption and obesity, while an abundance of material possessions can foster a sense of entitlement and dissatisfaction.

Finding the Balance

Abundance can be a blessing when used wisely and in moderation. The key is to strike a balance between having enough and having too much. This requires careful consideration of our needs, values, and the potential consequences of our actions.

It’s important to remember that true abundance is not merely about accumulating more and more, but about finding contentment and fulfillment with what we have. By seeking balance and avoiding the pitfalls of excess, we can create a life that is both rich in resources and rich in meaning.

Moderation: The Art of Balance and Avoiding Extremes

In the realm of life, striving for moderation is akin to walking a tightrope – always seeking balance and avoiding the perils of excess and deficiency. It’s a delicate dance, but one that can lead to a life filled with harmony and contentment.

The Importance of Balance

Moderation is the golden mean, the middle path between extremes. It’s about finding a balance in all aspects of life, whether it’s our consumption, our relationships, or our spending. When we embrace moderation, we avoid the pitfalls of both deficiency and excess, ensuring a life that is both fulfilling and sustainable.

Extremes: Excess and Deficiency

Excess and deficiency are the two extremes that moderation steers clear of. Excess, like a raging river, can overwhelm us, leaving us feeling depleted and lost. Deficiency, on the other hand, is like a stagnant pond, leaving us feeling empty and unfulfilled.

Moderation is the antidote to these extremes. It’s about finding the sweet spot where we have enough to satisfy our needs without drowning in abundance or depriving ourselves of essentials.

Contextual Appropriateness

Moderation is not a one-size-fits-all concept. What may be considered moderate in one context may be excessive or deficient in another. For example, the amount of food that is moderate for a marathon runner may be excessive for a sedentary desk worker.

In determining moderation, it’s crucial to consider the context and what’s appropriate in each situation. This requires a keen sense of awareness and an ability to adapt to changing circumstances.

By embracing moderation, we live a life of balance and fulfillment. We avoid the extremes of excess and deficiency, finding harmony and contentment in the middle ground. It’s a journey that requires constant self-reflection and adjustment, but the rewards are immeasurable – a life lived in balance and peace.

Excess: A Tale of Imbalance and Consequences

In the realm of measurement, excess stands as a cautionary tale. It is the realm beyond abundance, where the bounds of what is adequate are transgressed. Excess is a state of imbalance, where the scales tip too far in one direction.

The consequences of excess are manifold. It can lead to deficiency in other areas, as resources are diverted towards the excessive pursuit. It can disrupt balance, creating a ripple effect that disrupts the harmony of the whole.

For instance, consider the story of the farmer who sowed excess seeds in his field. Driven by a desire for an overflowing harvest, he scattered handfuls of seeds generously. However, the resulting forest of seedlings choked each other out, leaving him with a meager yield. His excess had led to deficiency, as the plants competed for sunlight and nutrients.

Excess can also breed indulgence and waste. When we have more than we need, we may be tempted to squander it on unnecessary luxuries. This not only depletes our resources but also distorts our perception of what is truly valuable.

The antidote to excess is moderation. It is the art of finding the golden mean, where the needs of the moment are met without overdoing it. Moderation teaches us to appreciate the sufficiency of what we have and to avoid the pitfalls of both deficiency and excess.

Remember, excess is not simply an abundance of something good. It is an imbalance that can have far-reaching consequences. By embracing moderation and seeking a harmonious balance, we can avoid the excesses that lead to depletion, waste, and regret.

Deficiency: A Shortfall That Disrupts Equilibrium

In the realm of measurement, deficiency stands as a stark contrast to its counterpart, abundance. It represents a shortfall, a glaring lack that disrupts the delicate balance of adequacy. Deficiency manifests itself in myriad forms, be it in the scarcity of resources, the absence of crucial skills, or the inadequacy of knowledge.

Like a threadbare garment that fails to provide warmth, deficiency unveils itself as an imbalance. It is the opposite of excess, yet it shares an inherent kinship with it. For just as excess can lead to chaos, deficiency can sow the seeds of stagnation and despair.

When confronted with a deficiency, it is easy to become entangled in a vicious cycle of frustration and inadequacy. The perception of lack can distort our judgment, leading us to believe that there is never enough. However, it is crucial to remember that deficiency is not a permanent state of being. Like all things, it can be addressed and overcome.

To bridge the gap between deficiency and adequacy, context plays a pivotal role. Understanding the circumstances that have contributed to the shortfall can provide valuable insights into potential solutions. By examining the broader picture, we can identify underlying causes and develop tailored strategies to address them.

Subjectivity also comes into play when evaluating deficiency. Our personal experiences and biases can shape our perception of adequacy. What may seem like a deficiency to one person may be viewed as sufficient by another. Recognizing the influence of subjectivity allows us to approach the issue with greater objectivity and understanding.

To break free from the clutches of deficiency, objectivity is paramount. By relying on facts, evidence, and unbiased assessments, we can create a foundation for informed decision-making. Verifiable information and supporting data empower us to make rational judgments that lead to meaningful improvements.

Embracing the principles of objectivity, context, and a growth mindset, we can transform deficiency into a catalyst for progress. By acknowledging the shortfall, seeking out solutions, and embracing a positive outlook, we can bridge the gap and restore a sense of equilibrium to our lives and endeavors.

Appropriateness: The Key to Good Measure

In the realm of measurement, appropriateness reigns supreme. It’s not just about hitting a target but about considering the context, suitability, and relevance of the measure to the situation at hand.

Imagine you’re hosting a dinner party for ten guests. Adequacy would dictate that you prepare enough food to satisfy their hunger, while abundance would mean overflowing plates with leftovers. But appropriateness takes it a step further. It suggests that you consider the preferences of your guests, the occasion, and the overall ambiance you wish to create. A simple yet elegant meal might be more appropriate than an extravagant feast.

Subjectivity plays a role in determining appropriateness. What is suitable for one person may not be for another. A minimalist might find a tiny apartment to be perfectly adequate, while an extrovert could crave a spacious home for entertaining. Objectivity, on the other hand, relies on facts, evidence, and unbiased assessments. Evaluating the specific needs and circumstances of a situation can help determine an objective measure of appropriateness.

For example, a doctor measuring the dosage of a medication must consider the patient’s age, weight, and medical history to ensure an appropriate dosage. This is an objective assessment based on established standards and guidelines.

In conclusion, appropriateness is the cornerstone of good measure. By carefully considering the context, suitability, and both subjective and objective factors, we can ensure that our measurements align precisely with our intentions and the desired outcome. Remember, it’s not just about the quantity but about the perfect fit for the occasion.

Balance: The Key to a Harmonious Measure

In the realm of measurement, there lies a delicate dance between excess and deficiency. Balance emerges as the guiding principle, orchestrating a harmonious equilibrium among elements.

To grasp the essence of balance, let us delve into the world of scales. As the weights on either side come into perfect alignment, a state of equilibrium is achieved. This balance ensures accuracy and fairness in measurements.

Similarly, in our everyday lives, balance plays a pivotal role in determining the appropriateness of measure. Consider the task of deciding the amount of salt to add to a dish. Too little salt leaves the dish bland, while excessive salt can overpower its delicate flavors. It is only through a careful balance that the perfect taste is achieved.

Balance extends beyond material measures to encompass our intangible experiences. In relationships, for instance, a healthy balance between closeness and independence is crucial for harmony. Work-life balance, too, requires a delicate equilibrium to prevent burnout and maintain overall well-being.

Striking the right balance often requires a keen eye for context. What is considered adequate in one situation may be excessive in another. For example, the appropriate amount of time spent on a hobby might vary depending on one’s personal responsibilities and interests.

Achieving balance is not always straightforward. We may be swayed by our subjective preferences and biases, leading to imbalances. However, by striving for objectivity and considering all relevant factors, we can make more informed and balanced decisions.

Remember, the path to a harmonious measure lies in finding the delicate equilibrium between extremes. By embracing balance, we unlock the power to create a world where everything is in its proper place, creating a sense of order, harmony, and well-being.

Context:

- Discuss the influence of specific circumstances on measure perception.

- Relate context to appropriateness and subjectivity.

Context: The Lens Through Which We Measure

The concept of “good measure” is intricately intertwined with the specific circumstances that surround it. Like a chameleon, measure adapts its meaning to fit its context.

For instance, consider the amount of food we serve ourselves. At a family gathering, where love and abundance prevail, we may fill our plates with generous helpings that spill over the edges. In contrast, at a formal dinner party, we might opt for a more subtle and restrained approach, leaving room for conversation and dessert.

The context also shapes our perception of what constitutes an adequate measure. In a remote village where resources are scarce, a small portion of food may be seen as plenitude. Yet, in a bustling metropolis, the same portion might be dismissed as meager.

Moreover, context influences our subjectivity. What seems excessive to one person may be necessary to another. A marathon runner may need to consume vast amounts of fluids to sustain their performance, while a sedentary office worker may find the same quantity overwhelming.

To truly understand the meaning of good measure, we must consider the context in which it is applied. By recognizing the unique circumstances that shape our perceptions, we can make appropriate and balanced judgments about what constitutes an ideal measure.

**Subjectivity: The Role of Personal Perspectives**

In the realm of measurement, the concept of subjectivity plays a crucial role in shaping our perception of what constitutes a “good measure.” Subjectivity refers to the influence of personal judgments and biases on our assessment of adequacy. It acknowledges that our experiences, values, and beliefs inevitably color the way we evaluate measures.

Perspective Matters:

Each individual brings a unique perspective to the table when determining what is an appropriate measure. This perspective is influenced by our background, culture, and life experiences. For instance, a chef may prioritize abundance in ingredients to ensure a flavorful dish, while a health-conscious individual might advocate for moderation to promote well-being.

The Power of Biases:

Biases, both conscious and unconscious, can further skew our subjective judgments. We tend to favor information that confirms our existing beliefs and discount evidence that contradicts them. This can lead us to overestimate or underestimate the adequacy of a measure based on our biases.

The Role of Opinion:

Subjectivity also involves the influence of personal opinions. Opinions are formed through our interactions with others and the information we encounter. They can be based on hearsay, anecdotal evidence, or simply gut instinct. While opinions can provide valuable insights, they should be carefully weighed against objective data to avoid subjective distortions.

Balancing Subjectivity with Objectivity:

Recognizing the role of subjectivity is essential for making informed and balanced judgments about measures. It allows us to account for the influence of personal factors and biases. However, it is equally important to strive for objectivity, based on facts, evidence, and unbiased assessments. By considering both subjective and objective perspectives, we can make more informed and well-rounded decisions.

In conclusion, subjectivity is an inherent part of measuring and evaluating adequacy. While it can introduce biases and variations in perception, it also brings valuable perspectives that can enrich our understanding of what constitutes a “good measure.” By embracing the role of subjectivity and balancing it with objectivity, we can make more informed and balanced judgments that serve our diverse needs and contexts.

Objectivity: The Measure of Truth

Objectivity is the bedrock of accurate measurement. It relies on unbiased assessments, verifiable information, and supporting data. When we strive for objectivity, we seek to remove personal preferences and biases from our evaluations.

Facts and evidence form the foundation of objectivity. We gather information from reliable sources, scrutinize it for accuracy, and present it without distortion. By relying on factual evidence, we minimize the influence of subjective perceptions and personal opinions.

Objectivity also encompasses freedom from preferences. We strive to present information impartially, without allowing our own biases to color our conclusions. We recognize that different perspectives exist and present them fairly, allowing readers to form their own informed opinions.

The pursuit of objectivity is essential for accurate measurement in all aspects of life. Whether we are assessing the quality of a product, evaluating the performance of an employee, or making decisions that impact our society, objectivity provides a reliable and unbiased guide.

In the realm of measurement, objectivity ensures that our standards are fair, equitable, and free from prejudice. It allows us to compare outcomes accurately and make informed decisions that benefit everyone.

When we embrace objectivity, we cultivate a culture of truthfulness and accuracy. We create a foundation for trust, understanding, and progress. In a world often clouded by subjectivity, objectivity provides a beacon of clarity, helping us navigate complex issues and make meaningful decisions.