Exceptions To The Statute Of Frauds: Ensuring Contract Enforceability

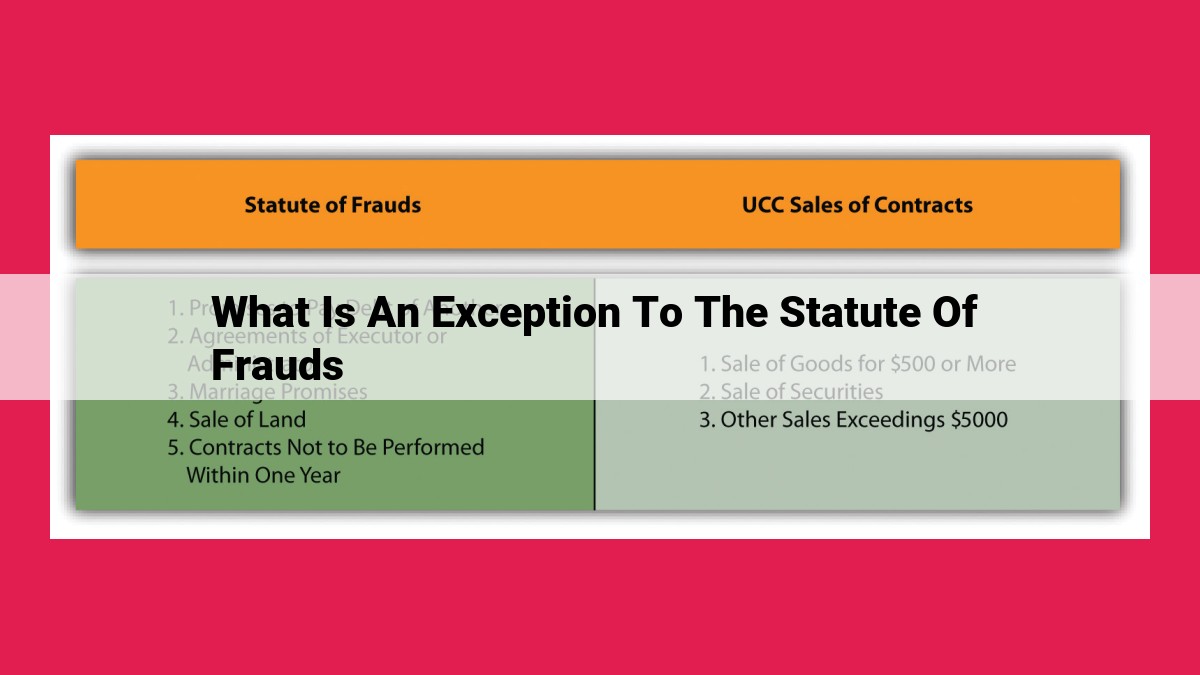

Exceptions to the statute of frauds allow for the enforcement of certain contracts even if they are not in writing. These exceptions include: written promises, contracts for the sale of goods over a certain value, contracts fully performed, contracts based on reliance, and estoppel. Understanding these exceptions is crucial for ensuring that contracts are enforceable, even if they do not meet the statute of frauds’ general requirement for written form.

Navigating the Exceptions to the Statute of Frauds

In the realm of contracts, the Statute of Frauds stands as a guardian against fraud and false claims. It mandates that certain agreements be documented in writing to be legally binding. However, life’s complexities often necessitate exceptions to this rule, providing pathways for parties to enforce oral contracts under specific circumstances.

The Statute of Frauds serves a vital purpose: preventing deceitful parties from fabricating verbal agreements to their advantage. By requiring written contracts for specific types of transactions, the statute provides tangible evidence of the parties’ intentions, safeguarding against misunderstandings and potential exploitation.

Yet, there are situations where an oral contract has been partially or fully executed, and denying its enforceability would result in injustice. For these instances, the law recognizes exceptions to the Statute of Frauds, allowing aggrieved parties to seek legal recourse even without a written agreement.

Promises Made in Writing

- Explain that contracts signed by both parties or contained in written documents are enforceable.

- Discuss the benefits of having written contracts.

Promises Made in Writing: Exception to the Statute of Frauds

In legal matters, the Statute of Frauds serves as a shield against fraud, requiring certain types of contracts to be in writing to be enforceable. However, there are exceptions to this rule, and written contracts stand as a shining example.

Imagine yourself at a bustling market, eager to seal a deal for a prized antique. Without a written contract, your oral agreement could vanish into thin air if the seller changes their mind. But fear not, the written word holds the power to bind parties to their commitments.

Contracts that bear the signatures of both parties or are contained in written documents are legally enforceable. This safeguard ensures that both parties have a clear understanding of the terms and conditions, minimizing misunderstandings and disputes down the road.

Written contracts offer numerous benefits. They provide a tangible record of the agreement, eliminating he-said-she-said situations. Written contracts also serve as valuable evidence in case of any legal challenges, protecting your interests and ensuring the fulfillment of obligations.

So, if you’re entering into an important agreement, don’t rely on verbal promises alone. Put it in writing to safeguard your rights and avoid the potential pitfalls of the Statute of Frauds. Let the written word be your ally in the intricate world of contracts.

Contracts for the Sale of Goods and the Statute of Frauds: A Buyer’s Guide

In the realm of contract law, the Statute of Frauds stands as a formidable guardian, ensuring that certain types of agreements are put into writing to prevent fraud and misunderstandings. However, not all contracts fall under the statute’s watchful eye. One notable exception is contracts for the sale of goods.

Enter the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC), a comprehensive set of laws governing commercial transactions, including the sale of goods. The UCC recognizes the importance of streamlining business dealings and reducing uncertainty, and thus provides an alternative path for enforcing certain types of contracts, even if they are not in writing.

One crucial aspect of the UCC is its writing requirement. For contracts involving the sale of goods worth over $500, the law mandates that such agreements be written. This written documentation serves as undeniable proof of the parties’ intentions and protects both buyers and sellers from potential disputes or misunderstandings.

However, even if a contract for the sale of goods does not exceed $500, it is highly advisable to put it in writing. A written contract provides a clear and concise record of the terms agreed upon, reducing the likelihood of future disagreements and ensuring that both parties are on the same page.

By understanding the nuances of the Statute of Frauds and the UCC’s writing requirement, buyers and sellers can navigate the complexities of contract law with confidence. Remember, a little bit of ink can go a long way in safeguarding your business interests and ensuring smooth and enforceable transactions.

Contracts Fully Performed: An Exception to the Statute of Frauds

In the legal realm, the Statute of Frauds serves as a crucial safeguard, demanding that certain types of contracts be documented in writing to prevent potential disputes. However, this rule is not absolute, and there are a few notable exceptions. One such exception is for contracts that have been fully performed.

Imagine two friends, Alice and Bob, who verbally agreed to paint Alice’s house for $1,000. Although their agreement was not put into writing, they proceeded with the project and Bob diligently completed the painting. In this scenario, the contract would be considered fully performed, and the Statute of Frauds would not bar Alice from being held accountable for payment.

The rationale behind this exception is simple: when a contract has been fully executed, the parties have already fulfilled their obligations. The need for a written document becomes less critical because there is tangible evidence of the work that has been done.

Other examples of fully performed contracts include:

- Completed Sale of Goods: If you purchase an item from a store and pay for it in full, the contract is considered fully performed even if it was not written down.

- Paid-for Services: When a service provider completes the agreed-upon work and you pay for it, the contract is fully performed, regardless of whether it was in writing.

- Fulfilled Leases: If a tenant moves into a rental property and pays rent until the end of the lease term, the contract is fully performed even if it was not written down.

It’s important to note that this exception only applies to contracts that have been fully executed. If only partial performance has occurred, the Statute of Frauds may still apply. Therefore, it’s always advisable to document agreements in writing to avoid any potential legal complications.

Contracts Based on Reliance: An Exception to the Statute of Frauds

Imagine this scenario: you’ve spent countless hours discussing a business venture with a potential partner, building castles in the air and pooling your resources in preparation for this promising collaboration. Yet, to your dismay, they abruptly pull the plug, leaving you with shattered dreams and substantial financial losses. You’re left wondering, “Is there any legal recourse? How can I hold them accountable for their broken promises?”

Enter the Doctrine of Reliance

There is a glimmer of hope in such situations: the doctrine of reliance. This exception to the statute of frauds allows you to enforce contracts based on the principle of detrimental reliance.

What is Detrimental Reliance?

Detrimental reliance means that you, known as the relying party, have suffered a financial or other loss because you reasonably relied on the other party’s promise to enter into a contract. The loss you sustain must be a direct result of your reliance on the promise.

Requirements for Proving Reliance

To successfully prove reliance, you must demonstrate the following:

- You reasonably relied on the other party’s promise, expecting them to fulfill their end of the bargain.

- Your reliance was to your detriment, meaning you suffered a significant loss or hardship as a direct consequence.

- You communicated your reliance to the other party, either through words or actions.

Potential Consequences

If you can prove detrimental reliance, the court may order the other party to fulfill the contract or compensate you for your losses. This remedy is intended to prevent injustice and restore the status quo that existed before the promise was broken.

Importance for Contractual Agreements

The doctrine of reliance is a crucial safeguard for parties who enter into informal or partially written contracts. It ensures that those who have acted in good faith and suffered losses due to a broken promise can seek legal recourse.

Remember, the statute of frauds is not an impenetrable fortress. Under certain circumstances, the doctrine of reliance provides an essential escape route, allowing you to enforce contracts that would otherwise be unenforceable. If you find yourself in a similar situation, seek legal advice to explore your options and protect your rights.

Estoppel: Overcoming the Statute of Frauds with Fairness

Imagine this scenario: John verbally agrees to sell his vintage car to Sarah for $20,000. However, John changes his mind and refuses to sign a written contract as required by the Statute of Frauds. Dismayed, Sarah believes she has no recourse since the contract is not in writing.

But wait! There’s a silver lining. Sarah can argue that John is estopped from invoking the Statute of Frauds. Estoppel is a legal doctrine that prevents a person from asserting a technical defense (like the Statute of Frauds) when their own actions or words have led another party to reasonably rely on the existence of a contract.

For example, if John had repeatedly assured Sarah that he would sell her the car and even allowed her to drive it for a week, Sarah could argue that John’s conduct sufficiently indicated his willingness to enter into a binding agreement. By relying on John’s representations, Sarah has suffered a detriment (the loss of the opportunity to buy the car from someone else).

Therefore, the court may hold John estopped from using the Statute of Frauds as a defense. This is because his actions have essentially created an implied contract that is both fair and enforceable.

In essence, the doctrine of estoppel ensures that the Statute of Frauds does not become a tool for injustice. It allows parties to enforce contracts that may not meet all of the formal requirements but are nevertheless supported by reasonable reliance and fair dealing.