Classical Vs. Operant Conditioning: Understand The Key Differences And Applications

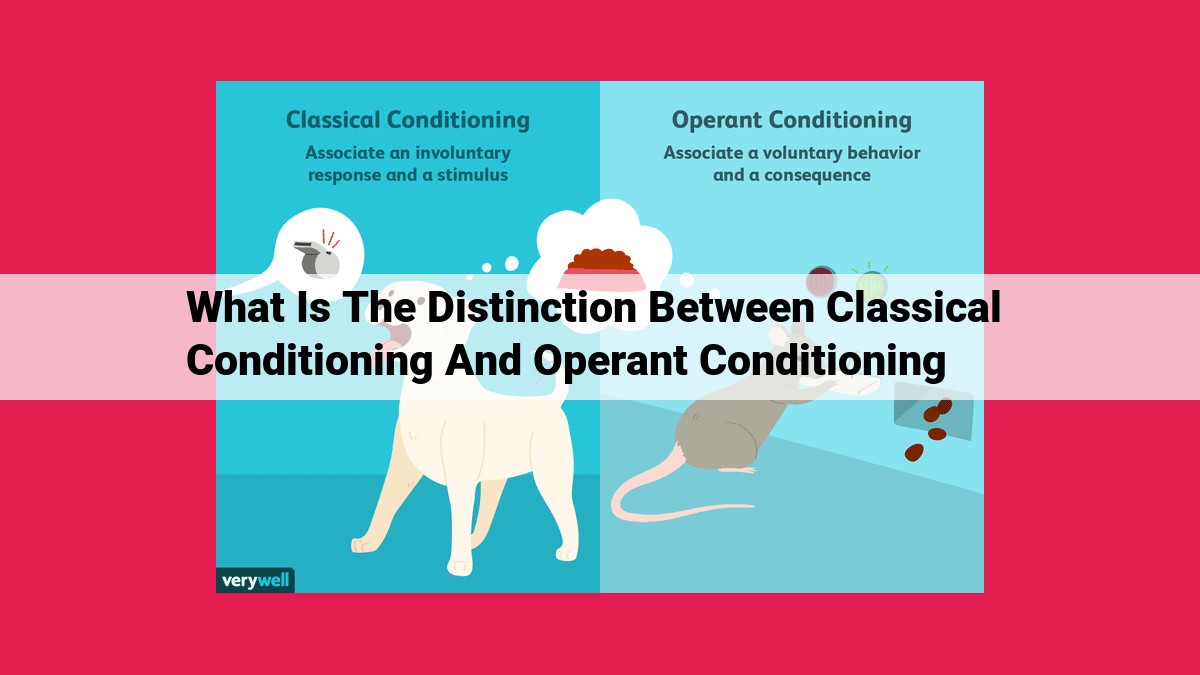

Classical conditioning establishes an association between a previously neutral stimulus and a reflex-eliciting stimulus, resulting in a conditioned response. Operant conditioning reinforces desired behaviors through consequences (reinforcement/punishment), shaping them over time. Classical conditioning involves involuntary responses, while operant conditioning involves voluntary responses influenced by their consequences. In summary, classical conditioning links stimuli to responses, while operant conditioning modifies behaviors based on their outcomes.

Classical and Operant Conditioning: The Pivotal Duo of Behavior Modification

We’ve all experienced moments where a certain sound or smell instantly triggers a memory or a specific action. Or perhaps, there have been times when a particular reward or punishment has shaped our behavior in some way. These phenomena, so deeply ingrained in our lives, are the result of two fundamental learning processes known as classical and operant conditioning.

Classical Conditioning: A Story of Association

Imagine the Pavlov’s dogs experiment. A dog is presented with food, a natural stimulus that elicits a response: salivation. Over time, the dog learns to associate the sound of a bell, a previously neutral stimulus, with the food. The bell alone eventually triggers salivation, demonstrating how the dog has made a connection between the two stimuli.

This is the essence of classical conditioning: the pairing of a neutral stimulus with an unconditioned stimulus (a stimulus that naturally evokes a response) to create a conditioned stimulus that elicits a conditioned response. It’s all about the power of association.

Operant Conditioning: The Principle of Reinforcement

On the other hand, operant conditioning focuses on the consequences of our actions. When a certain behavior leads to a desirable outcome, we’re more likely to repeat it. Conversely, if a behavior has negative consequences, we’re less inclined to perform it again.

Reinforcement and punishment play crucial roles in operant conditioning:

- Reinforcement strengthens desired behaviors. It can be positive (e.g., giving praise) or negative (e.g., removing an unpleasant stimulus).

- Punishment weakens undesired behaviors. It can be positive (e.g., administering a mild shock) or negative (e.g., taking away a privilege).

Distinguishing Between the Two

While both conditioning types involve learning through experience, they differ in several key ways:

- Antecedent: Classical conditioning deals with events that precede behavior, while operant conditioning focuses on consequences that follow behavior.

- Type of Response: Classical conditioning elicits involuntary responses, while operant conditioning modifies voluntary behaviors.

- Role of Reinforcement: Reinforcement is essential for operant conditioning, but not for classical conditioning.

Applications in the Real World

Classical conditioning has been used to treat phobias by associating negative stimuli with relaxation techniques. It has also been effective in developing aversions to harmful substances like tobacco.

Operant conditioning is widely applied in behavior modification, shaping everything from healthy eating habits to workplace productivity. It’s also extensively employed in animal training.

Classical and operant conditioning are indispensable concepts that help us understand the intricate mechanisms behind learning and behavior modification. They offer a powerful toolkit for shaping our own behaviors, influencing others, and improving the lives of both humans and animals. By harnessing their principles, we can foster a better, more fulfilling world.

Understanding Classical Conditioning: Defining Conditioned and Unconditioned Stimuli and Responses

Classical conditioning, a fundamental concept in psychology, revolves around the association of unconditioned stimuli (events that naturally trigger a response) with conditioned stimuli (initially neutral events). This pairing leads to the development of conditioned responses.

Imagine the ringing of a bell (unconditioned stimulus) that triggers salivation in a dog (unconditioned response) when food (natural reinforcer) is given shortly after. If the bell is repeatedly paired with food, the dog will eventually start to salivate (conditioned response) even when only the bell is presented (conditioned stimulus). This process is known as classical conditioning.

Unconditioned Stimulus (US): The bellringing that triggers the dog to salivate only when paired with food is considered an unconditioned stimulus.

Unconditioned Response (UR): Salivation in response to the bell before the conditioning.

Conditioned Stimulus (CS): The bell’s sound is initially a neutral stimulus that pairs with the unconditioned stimulus to produce a conditioned response.

Conditioned Response (CR): After learning, the dog salivates in response to the sound of the bell even if no food is presented.

Understanding Classical Conditioning: The Power of Association

Embarking on a Journey of Classical Conditioning

Classical conditioning, a form of associative learning, takes us on a fascinating journey into the world of linking stimuli to responses. At the helm of this process is Ivan Pavlov, a renowned physiologist who stumbled upon this phenomenon while studying digestion in dogs. Pavlov’s experiment inadvertently unveiled the intricate connection between a dog’s salivation (an unconditioned response) to the presence of food (an unconditioned stimulus) and the sound of a bell (which would later serve as a conditioned stimulus).

The Dance of Stimuli and Responses: Unraveling the Mechanisms

In the realm of classical conditioning, stimuli take on distinct roles. Unconditioned stimuli are those that naturally trigger a response without prior learning. Conditioned stimuli, on the other hand, are initially neutral stimuli that, through repeated pairing with unconditioned stimuli, acquire the ability to elicit similar responses. These responses, known as conditioned responses, mimic the unconditioned responses but are triggered by the conditioned stimulus.

From Fear to Aversion: A Tale of Classical Conditioning in Action

Throughout history, classical conditioning has played a pivotal role in shaping human behavior. One striking example is the development of phobias. John Watson, an influential psychologist in the early 20th century, conducted a controversial experiment known as the “Little Albert” experiment. In this experiment, Watson conditioned a young boy named Albert to fear white rats by pairing the presentation of a rat (unconditioned stimulus) with a loud noise (unconditioned stimulus). Over time, Albert exhibited a conditioned response of fear to the white rat (conditioned stimulus), even in the absence of the loud noise. This case serves as a poignant illustration of the power of classical conditioning in transforming neutral stimuli into potent triggers of emotional responses.

Understanding the Consequences of Behavior: Reinforcement and Punishment

In the realm of operant conditioning, consequences play a pivotal role in shaping our behaviors. Just as a gardener carefully tends to their plants, rewarding them with water for healthy growth, and even chastising them with a mild pruning for overgrowth, so too do consequences shape our actions.

There are two main categories of consequences: reinforcement and punishment. Each has its distinct effect on behavior, guiding us towards desirable outcomes and deterring us from undesirable ones.

Reinforcement: The Power of Positive Consequences

Positive reinforcement occurs when a desirable consequence is added after a desired behavior, increasing the likelihood of the behavior being repeated. Imagine a child who receives a sticker for tidying their room. The sticker, a pleasant reward, reinforces the behavior of tidying, making it more likely for the child to repeat it in the future.

Negative reinforcement is a bit more subtle. It occurs when an unpleasant consequence is removed after a desired behavior, also increasing the likelihood of the behavior being repeated. Think of a student who finishes their homework on time, earning the privilege of avoiding a dreaded chore. The absence of the chore serves as a negative reinforcer, encouraging the student to continue completing their homework on time.

Punishment: The Impact of Negative Consequences

Positive punishment is the addition of an unpleasant consequence after an undesirable behavior, decreasing the likelihood of the behavior being repeated. A classic example is a child getting scolded for talking in class, the scolding acting as a punishment to deter the child from repeating the behavior.

Negative punishment is the removal of a desirable consequence after an undesirable behavior, also decreasing the likelihood of the behavior being repeated. For instance, a teenager who stays out past their curfew may lose their allowance as a punishment. By removing a desired privilege, negative punishment aims to discourage the curfew violation.

The Delicate Balance: Reinforcement vs. Punishment

Understanding the consequences of our actions empowers us to shape our behaviors and those around us. However, it’s crucial to remember that reinforcement, when used appropriately, can foster positive growth and motivation, while punishment, if not applied judiciously, can lead to negative consequences and resentment.

Like a skilled gardener, we must find the right balance of encouragement and discouragement to cultivate the behaviors we desire. By harnessing the principles of reinforcement and punishment, we can create a more harmonious and fulfilling world for ourselves and others.

Shaping: The Art of Molding Behavior

Classical and operant conditioning, two fundamental pillars of behaviorism, provide essential insights into how we learn and modify our behaviors. While classical conditioning focuses on stimulus-response associations, operant conditioning delves into the power of consequences.

Shaping: A Gradual Approach

Shaping, a cornerstone technique in operant conditioning, involves breaking down a complex behavior into smaller, manageable steps. By gradually reinforcing desirable behaviors that are progressively closer to the desired goal, we can shape and alter behavior over time.

Steps in Shaping:

- Define the target behavior: Determine the ultimate behavior you want to achieve.

- Identify initial approximation: Start with a behavior that is slightly similar to the desired outcome.

- Reinforce each step: Reward any behavior that is closer to the target, even if it’s not perfect.

- Gradually increase difficulty: As the behavior improves, raise the bar by requiring more accurate approximations.

- Repeat until goal is reached: Continue reinforcing and refining behaviors until the target behavior is achieved.

Applications in Behavior Modification:

Shaping has wide-ranging applications in behavior modification:

- Teaching new skills: Break down complex skills into smaller steps, making learning more manageable.

- Modifying unwanted behaviors: Gradually reduce problematic behaviors by reinforcing desirable alternatives.

- Pet training: Train animals by shaping their behaviors using positive reinforcement.

- Therapy: Help individuals overcome phobias or develop healthy coping mechanisms by gradually introducing challenging situations.

Shaping, a cornerstone of operant conditioning, offers a powerful tool for modifying behavior. By gradually reinforcing desirable behaviors and refining them over time, we can shape and alter behavior to achieve desired outcomes in various aspects of our lives.

Distinguishing Classical from Operant Conditioning: Stimulus-Response Relationships

In the realm of conditioning, classical and operant conditioning stand as distinct approaches, each crafting its unique tapestry of stimulus-response relationships. Classical conditioning, pioneered by Ivan Pavlov, takes center stage in forging associations between initially neutral stimuli and naturally occurring responses. Famously, Pavlov’s dogs associated the sound of a bell (neutral stimulus) with the arrival of food (unconditioned stimulus), eliciting salivation (unconditioned response).

In contrast, operant conditioning, championed by B.F. Skinner, centers around the consequences of behavior, shaping actions through reinforcement and punishment. Here, the stimulus is the behavior itself, and the response comes in the form of either rewards (reinforcers) or punishments (aversive stimuli). For instance, rewarding a dog with a treat for sitting nicely strengthens that behavior.

Delving deeper, we uncover further contrasts. In classical conditioning, the stimulus-response connection is involuntary and reflexive. The sound of the bell automatically triggers salivation. However, in operant conditioning, the stimulus-response relationship is voluntary, dependent on the consequences of the behavior. The dog chooses to sit or not, influenced by the prospect of a treat or the avoidance of punishment.

Moreover, timing plays a crucial role in each conditioning type. In classical conditioning, the neutral stimulus must precede the unconditioned stimulus for the association to form. In operant conditioning, the consequences (reinforcement or punishment) must follow the behavior promptly for effective reinforcement.

Understanding these stimulus-response relationships empowers us to harness the power of conditioning in various settings. Classical conditioning can help us overcome phobias or create aversions, while operant conditioning serves as a valuable tool in shaping behavior, reducing unwanted actions, and training animals.

Understanding the Different Nature of Responses in Classical and Operant Conditioning

In classical conditioning, responses are automatic and involuntary. They are elicited by a conditioned stimulus that has been associated with an unconditioned stimulus. For example, if you hear the sound of a bell (conditioned stimulus) that has previously been paired with food (unconditioned stimulus), you may start to salivate (conditioned response) even before you see the food.

In operant conditioning, responses are voluntary and goal-directed. They are emitted by an organism in order to obtain a desired outcome or avoid an unwanted one. For example, if you push a button (operant response) and it delivers a food reward (reinforcer), you are more likely to press the button again in the future.

Reinforcement and Punishment in Operant Conditioning

Reinforcement increases the likelihood of a behavior being repeated, while punishment decreases its likelihood. There are two types of reinforcement:

- Positive reinforcement: Giving a reward after a desired behavior (e.g., giving a child a treat for cleaning their room).

- Negative reinforcement: Removing an unpleasant stimulus after a desired behavior (e.g., taking away a time-out when a child stops misbehaving).

There are also two types of punishment:

- Positive punishment: Giving an unpleasant stimulus after an undesired behavior (e.g., spanking a child for hitting their sibling).

- Negative punishment: Taking away a pleasant stimulus after an undesired behavior (e.g., taking away a child’s favorite toy for throwing it).

It’s important to note that punishment can be effective in the short term, but it does not teach new behaviors and can lead to negative side effects such as fear, aggression, and avoidance.

Practical Applications of Classical Conditioning: Treating Phobias and Developing Aversions

Classical conditioning, a fundamental learning theory, has proven invaluable in understanding and treating various psychological issues. One of its most notable applications lies in addressing phobias, irrational and intense fears, and developing aversions, negative associations with specific stimuli.

Treating Phobias with Classical Conditioning

Phobias are characterized by overwhelming, persistent fears that can significantly impair individuals’ daily lives. Classical conditioning offers a powerful approach to treating phobias known as exposure therapy. This technique involves gradually exposing individuals to the feared stimulus while simultaneously providing a positive or neutral experience.

Over time, the once-feared stimulus becomes associated with safety rather than fear. This process, known as counterconditioning, helps individuals overcome their phobias and live more fulfilling lives.

Developing Aversions with Classical Conditioning

Classical conditioning also finds practical applications in developing aversions, particularly in preventing harmful behaviors. One such application is aversion therapy, a technique used to reduce addictive behaviors like smoking or excessive drinking.

By pairing the addictive substance with an unpleasant experience, such as nausea or discomfort, classical conditioning creates a negative association with the substance. This aversion helps individuals curb their cravings and break free from addiction.

Applications and Benefits

The practical applications of classical conditioning extend beyond treating phobias and developing aversions. It has also been successfully employed in:

- Developing positive associations between food and healthy eating to promote healthy eating habits

- Reducing anxiety and stress through relaxation techniques like deep breathing exercises

- Enhancing memory and learning by associating new information with positive experiences

Classical conditioning remains a powerful tool for understanding and modifying human behavior. Its practical applications in treating phobias, developing aversions, and promoting positive behaviors have significantly improved the lives of countless individuals.

Unveiling the Power of Operant Conditioning: Shaping Behaviors and Unleashing Potential

In the realm of psychology, operant conditioning stands as a potent tool for molding behaviors, correcting undesirable actions, and even training animals. This conditioning technique, pioneered by B.F. Skinner, focuses on the consequences of actions, offering rewards (reinforcement) for desired behaviors and deterrents (punishment) for undesirable ones.

Consider the example of a child who repeatedly touches a hot stove and experiences pain as a consequence. Through operant conditioning, the child learns to associate touching the stove with unpleasant consequences and, thus, abstains from the behavior. This principle extends far beyond the simplistic example above, finding practical applications across various domains.

In classrooms, teachers employ operant conditioning by rewarding students for positive behavior, such as paying attention or completing assignments on time. Reinforcements, like praise or small rewards, encourage desired behaviors and promote a positive learning environment. Conversely, when students engage in disruptive behaviors, teachers may impose mild punishments, such as time-outs or loss of privileges, to reduce the likelihood of those behaviors repeating.

Animal training also heavily relies on operant conditioning techniques. Trainers use rewards, such as treats or praise, to reinforce desired behaviors, like sitting or staying. The concept of shaping plays a crucial role here, wherein small, successive approximations of the target behavior are rewarded, eventually leading to the desired result.

Operant conditioning is not limited to these examples. It has wide-ranging applications in therapy, behavior modification programs, and even organizational management. Understanding its principles empowers individuals to effectively shape their own behaviors, overcome challenges, and achieve desired outcomes.

In essence, operant conditioning offers a powerful tool for learning and behavior modification, enabling individuals to cultivate desired behaviors, shed unwanted habits, and harness their full potential by strategically managing the consequences of their actions.

Summarize the key points of classical and operant conditioning.

Classical and Operant Conditioning: A Tale of Two Learning Theories

Once upon a time, in the realm of psychology, there existed two rival theories that sought to unravel the mysteries of learning and behavior. These theories, known as Classical Conditioning and Operant Conditioning, each had its own unique approach to understanding how we respond to our environment. But like any good story, their paths would eventually intertwine, revealing a beautiful tapestry of complementary roles in shaping our actions.

Classical Conditioning: A Symphony of Associations

Imagine a dog named Rocky. Every day, his owner feeds him a bowl of kibble. Over time, Rocky learns to associate the sound of the bowl (unconditioned stimulus) with the arrival of food (unconditioned response). Soon enough, the mere sound of the bowl (conditioned stimulus) is enough to make Rocky’s mouth water (conditioned response), even when there’s no food in sight. This is the essence of classical conditioning: learning through association.

Operant Conditioning: Shaping Behavior with Consequences

Across the street from Rocky’s home lives a cat named Mittens. One day, Mittens discovers that when she jumps up on the counter (behavior), her owner gives her a tasty treat (reinforcement). This positive consequence strengthens the behavior, making Mittens more likely to jump up on the counter again in the future. Similarly, if Mittens scratches the furniture (behavior), she receives a spray of water (punishment), a negative consequence that weakens the behavior. This is the foundation of operant conditioning: learning through consequences.

The Dance of Learning: Classical vs. Operant

While both classical and operant conditioning involve learning, they differ subtly in their mechanisms. Classical conditioning focuses on stimulus-response relationships, where a previously neutral stimulus becomes associated with a meaningful response. In contrast, operant conditioning emphasizes behavior-consequence relationships, where the consequences of an action influence the likelihood of that action being repeated.

Matching the Theory to the Task

Just as each theory has its own unique approach, they also have distinct applications. Classical conditioning finds its niche in treating phobias and developing aversions, such as in the case of drug rehabilitation. Operant conditioning, on the other hand, excels in shaping behaviors, reducing unwanted behaviors, and training animals.

Far from being rivals, classical and operant conditioning are complementary forces that work in concert to shape our learning and behavior. Classical conditioning provides the foundation for understanding how we form associations, while operant conditioning elucidates the role of consequences in shaping our actions. Together, they offer a comprehensive framework for understanding the complexities of human and animal behavior.

Classical and Operant Conditioning: A Tale of Two Teachings

In the realm of psychology, two giants stand tall, their legacies intertwined: classical conditioning and operant conditioning. These two fundamental learning principles have shaped our understanding of how we acquire and modify behaviors.

Classical Conditioning: The Pavlovian Dance

Like the famous scientist Ivan Pavlov’s dogs, classical conditioning revolves around the idea that associations between stimuli can influence our responses. Imagine a dog that associates the sound of a bell with the arrival of food. Through repeated pairings, the bell alone can eventually trigger salivation, even in the absence of food. This is the essence of classical conditioning.

Operant Conditioning: Shaping Behaviors

Operant conditioning, on the other hand, focuses on the consequences of behaviors. When a desired behavior is followed by a positive outcome (reinforcement), it becomes more likely to be repeated. Conversely, when an undesirable behavior is followed by a negative outcome (punishment), it becomes less likely to occur. This principle forms the basis for countless techniques used in behavior modification.

A Complementary Duet

While classical and operant conditioning may appear distinct, they play complementary roles in shaping our learning and behavior. Classical conditioning establishes the associations between stimuli and responses, while operant conditioning reinforces or punishes those responses based on their outcomes.

Applications in the Real World

The insights from these conditioning principles have found wide applications in various fields:

- Classical conditioning: Treating phobias by changing the association between a feared stimulus and a neutral one.

- Operant conditioning: Training animals, reducing unwanted behaviors, and promoting positive habits.

Classical and operant conditioning are two inseparable pillars of our understanding of behavior. Their complementary nature underscores the complexity and richness of the learning process. By unraveling the mechanisms behind these principles, we gain the power to modify our own behaviors and forge our path toward desired outcomes.